You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘northern-ireland’ tag.

March 2025 marks 40 years since I left Ireland and became an accidental migrant to Australia.

I was honoured to be the speaker at the annual Saint Patrick’s Day Dinner of the Aisling Society, a group formed 70 years ago in Sydney to nurture cultural and historical aspects of the Irish-Australian tradition. It was a perfect opportunity to reflect on the major societal changes I’ve witnessed in that time, in both countries. I reproduce my talk below (I’ve linked to archival audio clips I used.)

It’s an honour to be asked to address you, almost 40 years to the day since I first set foot in Australia. I’ll be referring to three main themes today:

- the changing situation in Northern Ireland

- the altered state of the Catholic Church

- experiences of Indigenous Australians

and how these vexed topics have intersected with my own life as, now, an Irish-Australian.

I came here on what was meant to be a nine-month exchange between RTE and ABC Radio. I vividly remember getting the bus from the airport into Central, marvelling at how carefree the people heading to work seemed, in their light shirts and dresses. All the way in, I couldn’t take my eyes off the bus driver’s legs! I’d never seen a man in uniform wearing shorts before. Authority needed to be fully dressed at home.

At Central, I rang the only number I had in Sydney: Brendan Frost, an Irish sound engineer at the ABC.

Brendan’s wife told me he was already at work, on an outside broadcast with the Sydney Symphony, and to go straight there. Disbelievingly, I caught a cab – to the Sydney Opera House. At security, I expected to be stopped, but at the mention of Brendan’s name I was waved through. After listening to the orchestra in that awe-inspiring setting, it was time for a break. Brendan and his producer cracked a bottle of champagne in my honour.

That glowing bright morning, gazing through the glass at the rippling harbour, something inside me knew I wouldn’t be going back anytime soon.

The Ireland I left in 1985 was a miserable place. It wasn’t the grayness or the eternal rain – I’d had a year of that in Galway and still had a wild and wonderful time, pressed into service as secretary of the very first Galway Arts Festival, surrounded by music, madness, painters and poets. But in 1980 I joined RTE to train for my first REAL job – a producer on RTE Radio One. Ridiculously soon, I was producing the household names of national radio – Mike Murphy, Marian Finucane, Liam Nolan. My very first gig as a reporter was for the legendary Gay Byrne Show.

Just two years in, I was producing Morning Ireland, a breakfast show with astonishing reach in an era before commercial radio competed. A referendum had been announced, proposing an amendment to the Constitution to make abortion more illegal than it already was. The 1983 Amendment split families more than anything since the Civil War, 60 years before.

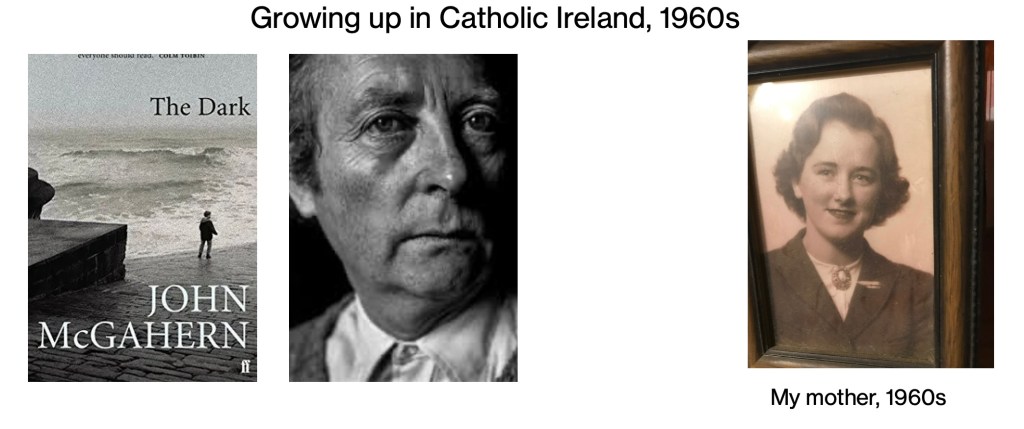

This was a time when, simply put, the Catholic Church ruled Ireland, hand in glove with the State. As we now know, there was SO much evil on their watch. Child abuse, orphaned and dead babies, women mouldering away in the Magdalene laundries. Outside, there was tacit approval of domestic violence within marriage and the exalted role of men, at work, in the home. No divorce, no contraception.

Some of our writers called it out: John McGahern, banned, his novel, The Dark, hidden in my mother’s wardrobe. And I should say here that while I would go on to loathe the abuses of power wielded by the Church hierarchy, I’ve managed to retain affection for some of the cultural rituals that formed what John McGahern beautifully described as the ‘sacred weather’ of a Catholic childhood.

Fintan O’Toole captures the era brilliantly in his memoir, We Don’t Know Ourselves. In 1958 Archbishop John McQuaid prevailed upon the Dublin Theatre Festival to drop a proposed adaptation of Joyce’s Ulysses from the program. They’d already dropped Sean O’Casey. Beckett withdrew his own work in protest. In the end the entire Festival was abandoned.

It was against this historical backdrop of censorship by the Catholic Church that I invited Anne Connolly, Director of a women’s health centre, the Wellwoman, to come on our Breakfast Show. The interview was fairly innocuous – presenter Marian Finucane stuck to the rules about not discussing controversial issues such as the coming Amendment because we were an entertainment, not a news, format.

But by lunchtime, I’d been suspended. Apparently someone from a powerful Catholic lay group rang the higher ups at RTE, to have me removed.

Little did they know what a favour they did me.

Twiddling my thumbs, I got interested in a forthcoming conference on Australia and Ireland, even becoming the honorary secretary. It was held at Kilkenny Castle and opened by a smart, sassy woman with a glint in her eye and steel in her voice. To me, she was a revelation. I decided there and then I wanted to go where the people in power were like her – not the men who ran the show at home.

Susan Ryan was a prominent figure in the Hawke government and chief architect of the world first Sex Discrimination Bill of 1984. She was also a lifelong supporter of Irish-Australian culture, as I was happy to find over subsequent years here. I’m delighted to see they commissioned a sculpture of her last year in the Rose Garden at Parliament House. I think Susan would enjoy this next chapter of my life, where past and present intersected in an unforeseen way.

Fast forward 30 years.

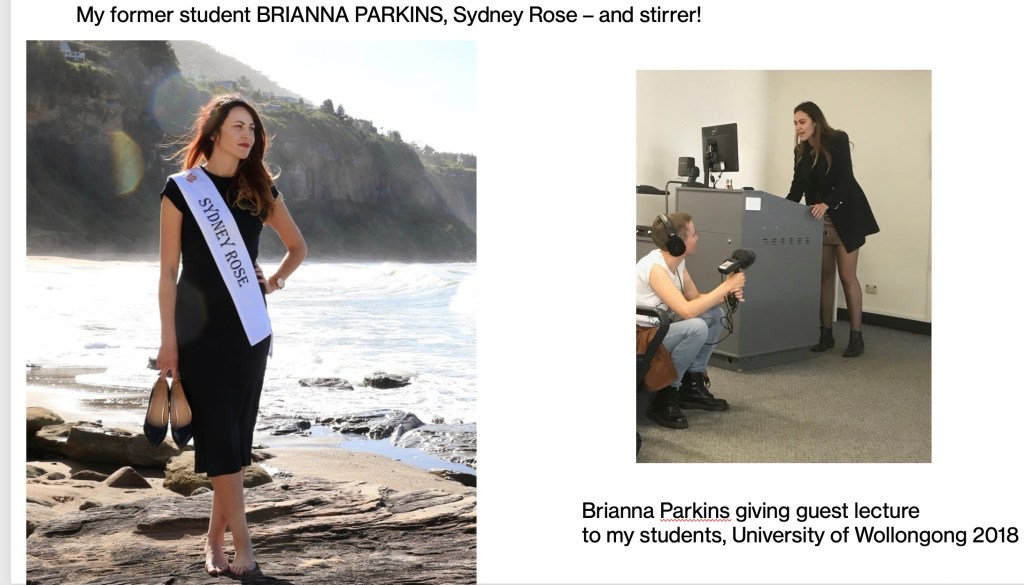

I’m teaching Journalism at the University of Wollongong, where I have a promising student called Brianna Parkins. Bri and I bonded in a kind of tough love way over journalism, feminism and Irishness. She was edgy and fun – and pretty radical.

So imagine my surprise when I saw her wearing a kind of Beauty Queen sash for a photo shoot event. She’d been selected as the Sydney Rose of Tralee. It made sense later – her grandparents hadn’t been back since they left the Liberties in Dublin 50 years earlier and couldn’t afford the fare. As the Rose, she got to bring them home before they died.

But while she was in Ireland, Bri caused controversy by getting embroiled in the budding campaign to Repeal the 8th Amendment – the Amendment against abortion that had been carried in 1983, the one that saw me thrown under a bus.

I told this circular story to Eleanor McDowall, a UK audio producer I met at a conference. Within weeks, she’d travelled to Australia to interview me and Bri for a radio documentary for BBC. Bri was coincidentally doing a guest lecture for my students that day.

The resulting documentary, A Sense of Quietness, has four female voices – Bri, me, Anne Connolly and an anonymous Irishwoman who’d recently gone to the UK for an abortion. It’s a marvel of concision and has won many accolades. Here’s Bri recounting how she livened up the usually bland proceedings of the Rose of Tralee Festival as it was broadcast LIVE on RTE – a huge television event, a bit like Eurovision.

SO MUCH HAS CHANGED in those four decades since I left. The Catholic Church is now on its knees, ordinary Catholics disgusted by the abuse, cruelty and scandals.

But weirdly, in Australia, despite describing myself on arrival as a refugee from the Irish Catholic Church, I was taking a different direction – towards, instead of away from, my culturally Catholic identity.

Because in Australia, I discovered, to be Irish WAS to be Catholic, whether you liked it or not. It didn’t seem to matter that as we know, a good 20% of Irish immigrants to Australia were Protestant of one kind or other. ‘Religion’ was code for politics: here, Irish meant Catholic and Protestant meant some variation of British.

I gradually learned the troubled history of the Irish as a maligned underclass in Australia. Sectarianism was evident from the earliest convict days, as Jeff Kildea and others have documented.

By the early 2000s, Australian demographics had shifted. Working at SBS with people of many ethnic backgrounds, I realised with dismay that to a Vietnamese or Indian Australian, this was all irrelevant – Irish and British were just lumped together in their minds as ‘White Australia’.

History retrofitted: Irish now lumped together with British as a mythical monolith called White/Settler Australia

Shocked by this retro-fitting of history, and the glossing over of colonial injustices perpetrated not once but TWICE on us, I researched the discrimination suffered by Irish Catholics for my doctorate.

I recorded oral histories with people at the heart of that bigotry: those involved in what most folk here will have called Mixed Marriages – a Catholic marrying a Protestant. They’re woven into a short series called Marrying Out. I’ll play just one clip here to illustrate, of Julia O’Brien and Errol White, who eloped to Sydney from Maitland in the 1940s. Their daughter, Susan Timmins, describes the enduring feud that followed.

Susan died not long ago, with Parkinsons, and her husband Peter followed last year. It’s such a loss, because people still need to hear this history. Only weeks ago I was judging podcast awards and one entry was an SBS series called Australia Fair, on Australia’s immigration history. It’s very good at recounting awful racism towards the Chinese, Pacific Islanders, postwar Europeans and more. Except for one stunning misrepresentation – the Irish are thrown in along with the Brits as part of some assumed monolith called White/Settler Australia.

But things HAVE of course changed hugely, for Irish-Australians, over the last 40 years. We certainly are now part of the Establishment, something that would likely make Robert Menzies turn in his grave. And as such, you’d hope we’d support those lower down the ladder, the latest wave of refugees and immigrants.

Not to mention Indigenous Australians.

I believe the Irish have a special affinity with Aboriginal Australians. It’s not just that we were co-colonised, through there IS that. It’s that we share a deep attachment to the land and its stories. I love the anecdote about the Aboriginal-Irish singer Kev Carmody, who was playing at a festival in I think Donegal. He went out early to check out the venue, a field in the middle of nowhere. A nosy farmer wandered over and pointed out a circular mound he called a Fairy Fort. Do you believe in Fairies, Kev asked. I do not, the farmer said indignantly. And after a minute: ‘but they’re there!’

I’ve been lucky enough to have gathered oral histories of Aboriginal Australians from artists in Arnhem Land to members of the Stolen Generations. One documentary I made is called: Beagle Bay, Irish nuns and Stolen Children. It tells the stories of several Aboriginal women, removed from their families as toddlers by government edict and raised by a branch of John of God nuns established by a County Clare sisterhood at Beagle Bay near Broome in 1908.

I arrived there in 2000, bristling with righteous rage – how dare these religious institutions kidnap and indoctrinate these kids. To my surprise, the Aboriginal women told me they loved the nuns who ‘grew them up’. Yes, they were devastated to have lost contact with their family and culture. But they refused to condemn the nuns themselves. Later I’d understand that the nuns and girls had bonded in solidarity against the sexist dispensations of the Church. Here’s a clip from one of those women, Daisy Howard, recalling her mixed feelings about her experiences.

I played clips of these Aboriginal women in Ireland, at a public lecture at University College Galway and at Pavee Point, an educational centre for Travellers (the marginalised group we used to call itinerants). As Daisy, from Halls Creek in the desert of Central Australia, described her conflicted feelings about her childhood, distance and difference didn’t matter. The Traveller women nodded and cried. That empathy was just as evident at Harvard, where I played the clips to a seminar at the Native American centre.

It taught me the universality of human suffering. The details about oppressor and oppressed change, but the lived experience is the same, just in different contexts.

Which brings me to Northern Ireland.

In my lifetime, N Ireland has moved through the civil rights movement of the late ‘60s to the era of occupying British forces, prolonged internment of men without trial and in the ‘70s and ‘80s, a terrible all out blitz of bombs and bullets and the horror and tragedy of the hunger strikes in 1981, when Bobby Sands and nine others died. British PM Margaret Thatcher remained intransigent, refusing to call them political prisoners. But public opinion changed, as it had back in 1916, when other Irish Republicans had died as martyrs. Over 3500 people would die before the historic Good Friday Peace Agreement of 1998.

What a moment.

In 2000, I went back to live in Ireland for a year so my two young sons could get a sense of the culture and get to know their numerous relatives. While there, I heard that Patrick Dodson, the senior Indigenous senator, was on a factfinding tour. I’d met Pat at home in Broome and he agreed to let me make a documentary about his trip.

He’d already been to Belfast to meet political activists on both sides. Once, he told me, he was in the office of David Ervine, a notorious former Loyalist paramilitary who was now a law-abiding politician. They were waiting for the Sinn Fein rep, who was late. Ervine called him and said: ‘Get down here and meet someone who claims to be even more oppressed than you are!’

Pat loved that black humour. I’ll come back to him and N Ireland later.

Overall – despite the chaos of the current world order and the travesty of having convicted rapist Conor McGregor as the VIP Irish guest in the White House for this recent St Patricks Day – I see positive changes in the last 40 years.

One, the demise of the Catholic Church’s untramelled power.

We may actually see a United Ireland

Two, we may actually see a United Ireland. If we do, its citizens will have to figure out how to live with a new pluralism – not just of Protestant Loyalists and Catholic Nationalists, but with the 9% of the population now born overseas, immigrants and refugees from all over the world.

My very first radio documentary for RTE in 1981, called In a Strange Land looked at the few thousand IMMIGRANTS then in Ireland. I was curious how they felt about being NOT part of the culturally almost homogenous Republic. They were mostly muddling through – not encountering prejudice so much as bewilderment. One African student told me how the children would run up and smear chalk on his arm, to see if it would turn black. He took no offence. It was born out of innocent curiosity, not hate.

Now, like the rest of the world and perhaps because it was unprepared for the infrastructure and support services these newcomers would need, Ireland has a strong anti-immigrant movement.

It has many obstacles to face: economic, social and political.

But how are my siblings and friends and their families faring compared to when I left in March 1985? They’re a thousand times better off. My best friend at the time ended up as a single mother in council housing, but she was able to buy it out and can afford the occasional RyanAir holiday in Europe to escape the weather. Her son is highly educated, a teacher himself now. EU laws ensure decent health and social services, not to mention unrestricted career options across Europe.

Ireland, of course, shares with this country pressing social problems such as violence against women, huge and growing inequality and a housing problem that seems as bad as our own here in Sydney.

But I’m not going to end on a pessimistic note. Like so many, I found opportunity here, a chance to follow your dream. I was so energised by the openness of this country, its willingness to take you as you were and give you the famed fair go, that I never wanted to return to the land of Who You Know that was Ireland.

By great good luck, a year after I arrived I was invited to research the history of the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Scheme, a nationbuilding project that was the de facto start of multicultural Australia. It would become my first book.

My Sidney Nolan Moment – but I missed it!

This slide shows the Dublin launch, at another Australia-Ireland conference in 1989. The man holding my book is the then Australian Ambassador to Ireland, Brian Bourke – who’d later be disgraced over corruption issues in WA. The man in the hat is Con Howard, the colourful former Irish consul in the US who somehow managed to pull together that first conference in 1983. And the man on the right… some of you might recognise him. I first met him just before the Kilkenny conference. Con was always hosting visiting Australians and I got roped into one of these long lunches. My job was simply to charm the visitor. But this man didn’t say much and I ran out of jokes. Groping to remember what his angle on Ireland was, I said, ‘I believe you paint?’ He smiled slightly. Yes. He did. I told him he should visit the West so, where the light was wonderful. It was only when I got to Kilkenny Castle and saw the magnificent Burke and Wills exhibition that I remembered his name: Sidney Nolan.

Amazingly, my book, The Snowy, won the NSW State Literary Award for Non-Fiction, which carried a prize of $15,000. As a freelance documentary maker I was then a virtual pauper. It miraculously became a deposit on my first home.

The Irish are no different from other migrants in that we all leave home in search of that simple yet elusive concept, A Better Life. Australia has given me that, in spades. I’m grateful to the generous people who guided me as a raw arrival, helped me see the beauty and complexity of this vast continent.

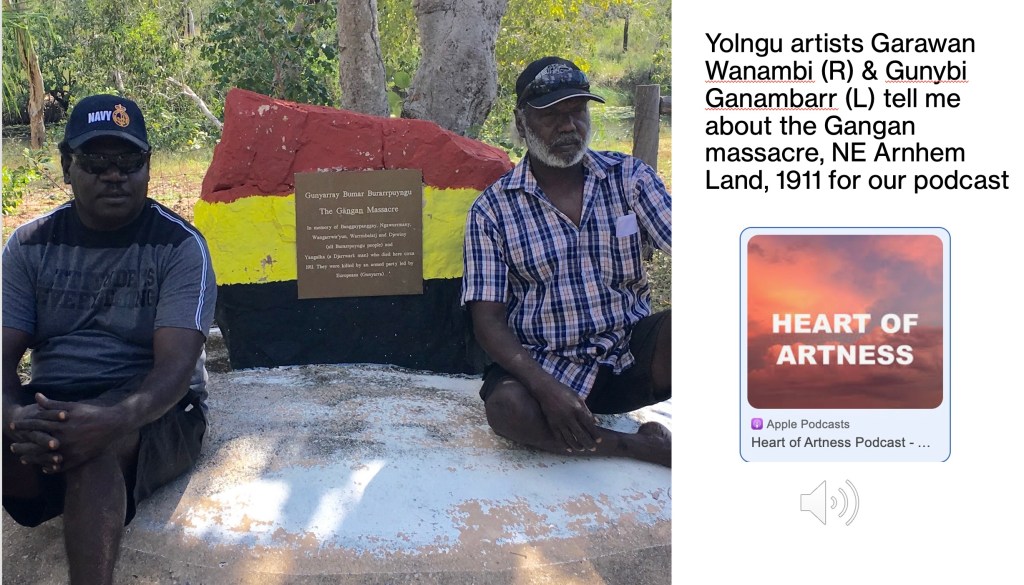

Ten years ago, I was invited to be part of an academic research project into the crosscultural relationships behind the production of Aboriginal art. It’s very important, culturally and economically, especially in remote communities. But little was known about the collaborative process between the black artists and largely white managers who ran the art centres. One centre we studied was at the Yolngu community at Yirrkala in NE Arnhem Land. I recorded oral histories there and compiled them as a podcast, Heart of Artness.

One of the most special moments in that project was when we were invited to a small community at a place called Gangan. The drive was 3 hours on a dirt road and the elder artist, Garawan, travelled with us. I ran out of small talk, and for some reason, looking at the ancient landscape, the stories of my youth came back to me. I told Garawan the Irish legend of the Salmon of Knowledge, my favourite. He listened quietly, then told me he ‘knew that story’. When we got to a waterhole near his home, he told me his water goanna lived there, ‘like your salmon’. It somehow created a bond, and Garawan must have decided to entrust me then with his own story – a dark one, about a massacre. It happened in 1911, by the river. Garawan, another brilliant artist, Gunybi, and a young ranger, Yinimala, also an artist, took me to the location.

I’ll play you a short clip – it opens with them speaking their language, Yolngu Matha. (Full analysis of that research project here, for anyone interested.)

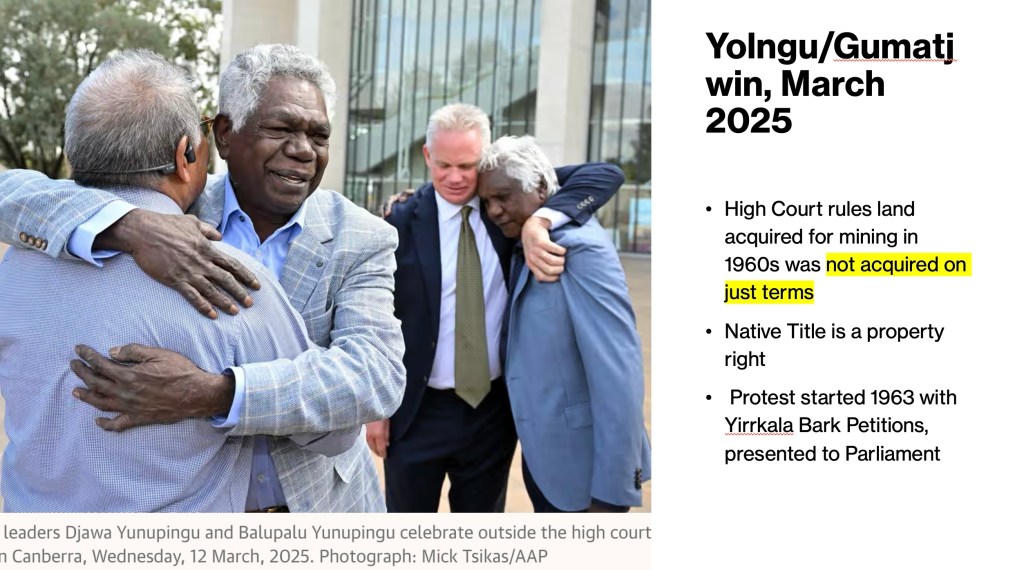

The country we drove through belonged to the Yunipingu family of the Gumatj clan – a famous family, known for the band Yothu Yindu and more. In 2019 the late Dr Yunipingu launched a Native Title case against encroachments by bauxite mines dating back to the ‘60s. In fact the Yolngu had protested the mines as far back as 1963, via two extraordinary bark petitions presented to Parliament in Canberra. Dr Yunipingu died two years ago. But just LAST WEEK, his brothers won a huge victory in the High Court on his behalf. It ruled that the Yolngu land had not been acquired ON JUST TERMS and that the community was owed substantial compensation. It’s as big a legal win as Mabo or Wik.

So I’m glad to be ending on a positive note – despite the bleak results of the Voice Referendum.

I’ll leave you with some thoughts on N Ireland, and words from someone far wiser than me.

From those first tentative years of peace, the situation has stabilised. We currently have a N Ireland First Minister from a post-conflict Sinn Fein background, Michelle O Neill.

Two significant points:

- Catholics now outnumber Protestants. The statelet was deliberately carved up so as to give Unionists a 2:1 majority. But the old taunt of Catholics breeding like rabbits has proved prescient.

- The 1998 Agreement allows that a referendum can be held on a United Ireland if a majority North and South wish.

That referendum seems increasingly likely. Several credible pundits think it may happen in the next 10 years.

I ended up back at the Sydney Opera House not too long ago, or at least observing it from the Museum of Contemporary Art, where I was interviewing Indigenous artist Richard Bell for our podcast, Heart of Artness. Richard has lost much of his culture and language. He gets his revenge on the coloniser by having them buy his art, in which he enunciates and excoriates their crimes. He’s gone from being a self-described derro in Redfern to the toast of the Tate.

As the Father of Reconciliation, Pat Dodson has had no happy ending. But he has the enduring satisfaction of knowing he fought the good fight, and he gave his all. He and others have laid the ground. I think we’ve all seen a hugely increased awareness across the country of the Indigenous presence – which when I came here, was so often invisible or ignored.

I want to end with a session I recorded outside Dublin around Christmas 2000, where Pat was the keynote speaker at a kind of Youth Retreat for Reconciliation funded by the EU to break down prejudice and bigotry of all kinds. There were high school kids there from north and south Ireland, Catholic and Protestant, and from the UK. After a day of workshops and talks by community leaders, one boy asked a question with the crystal clear innocence of youth: what was the solution to get a United Ireland.

The reply came from Matt, a self-described former Unionist heavy, now a youth worker for peace. Here’s his answer.

CLIP: MATT (1.17) (from Reconciliation, from Broome to Belfast, ABC 2001)

The next question came from a girl who described herself as a Pakistani Muslim from Birmingham. I’ll end with Pat Dodson’s response to her.

25 years on, it still sends shivers down my spine.

CLIP: PAT DODSON (from Reconciliation, from Broome to Belfast, ABC 2001)

Go raibh míle maith agaibh. (Thank you)

Thanks to Jeff Kildea, Mary Barthelemy and all at the Aisling Society and to Rosie Keane, Consul General, Consulate of Ireland, Sydney.