You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ category.

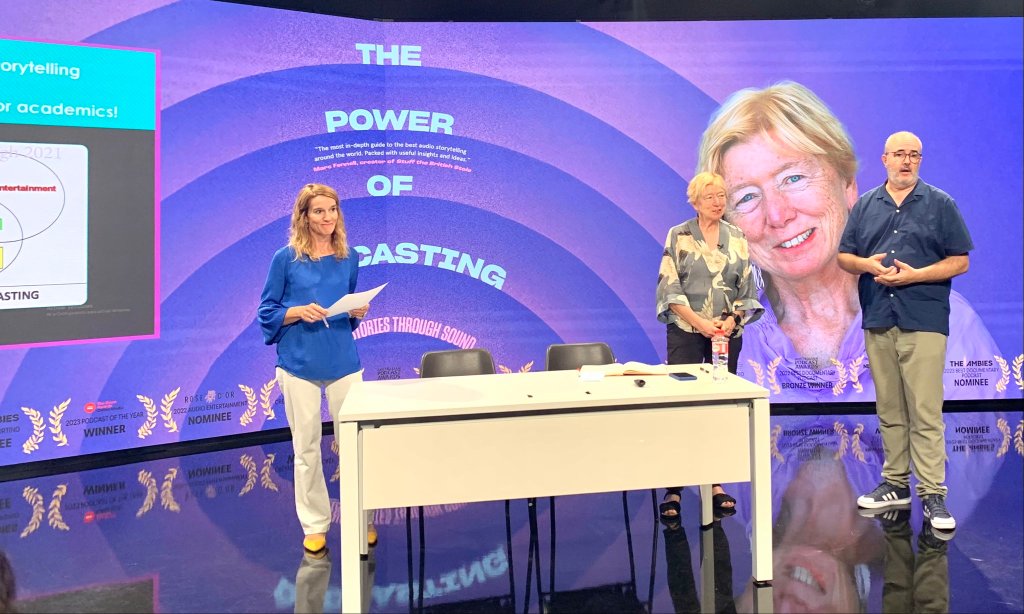

This year I was kept busy talking about podcasting – where it’s come from and where it’s headed. A highlight was getting to do a Masterclass in Narrative Podcasts in Dublin at the Irish Writers Centre, part of a Grand Tour of Europe, before heading back to SXSW Sydney and the True Story Festival in Coledale. The year ended with my traditional selection of Podcast Gems for The Conversation, ahead of an unusually cold Australian Christmas…

A standout this year was being interviewed at length by Canadian audio producer and thoughtful narrative podcast critic, Samantha Hodder, from Bingeworthy. Samantha had me reflect on new ways of audio storytelling and my role as an academic, producer, critic and advocate. She’s noticed that the worlds of academia and quality podcasts are increasingly intersecting – in a productive way – and traced that history back to early actions by a bunch of academics and audio enthusiasts, including me. Hard to believe RadioDoc Review is eleven years old now (check out the latest issue for in-depth reviews and essays on audio)! I also enjoyed talking about The Invisible Art of Podcasting with energetic US podcaster Florence Lumsden, host of The Format.

SXSW SYDNEY: PODCASTING and DEMOCRACY

At SXSW Sydney in October, I discussed the pressing topic of how democratic podcasting remains as a medium and how it is impacting democracy itself – huge themes, ably debated by our panel: redoubtable radio broadcaster and Professor of Journalism at UTS, Monica Attard, and her versatile colleague, Dr Sarah Gilbert, who oversees the excellent content at Impact Studios there (Check out Fully Lit, a new take on Australian writing!).

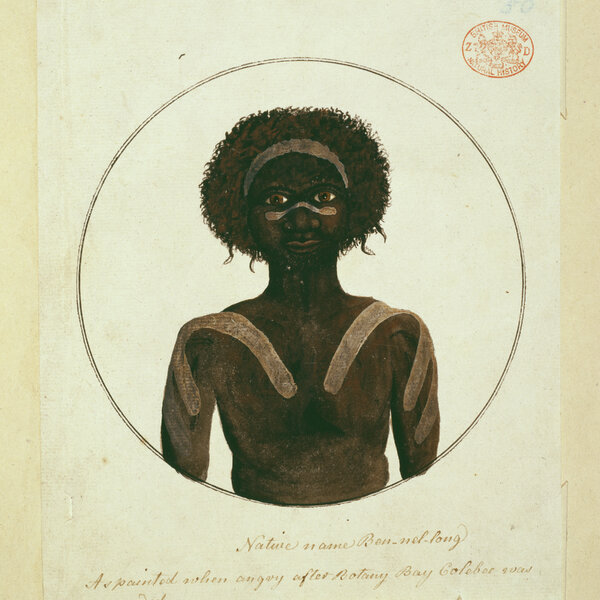

I was story consultant on one of Impact Studio’s provocative and informative podcasts, Unsettling Portraits, released in March. It explores the history of portraiture and colonialism, with academic hosts and historians of empire Kate Fullagar and Mike McDonnell reinterpreting this vexed issue with insights from Indigenous artists and historians in Australia, the Pacific and North America.

Image: Ben-nil-long. By James Neagle, 1798. Courtesy National Library of Australia. From Episode 2, Unsettling Portraits.

On a SXSW-related theme, I was pleased to contribute to a probing profile of US podcaster Lex Fridman, who has over 6 million listeners to his lengthy podcast interviews with international figures from politicians to tech execs. Writing in Columbia Journalism Review, author Maddy Crowell asks if this highly influential brand of podcast can be considered journalism. Definitely not, I told her:

“This is not journalism—it is glorified PR. Fridman facilitates his subjects to put forward aspects of themselves they would like to highlight. But that doesn’t necessarily mean we can’t gain some insights from his podcast.“

TRUE STORY WRITERS FESTIVAL, COLEDALE

In November, the fabulous True Story Festival at tiny Coledale south of Sydney hosted a wonderful range of writers, from historian Clare Wright on the remarkable Yolngu Bark Petitions of 1963 to the latest conspiracy theories, mulled over by a panel chaired by Fearless Flame Thrower Jan Fran, as she was introduced.

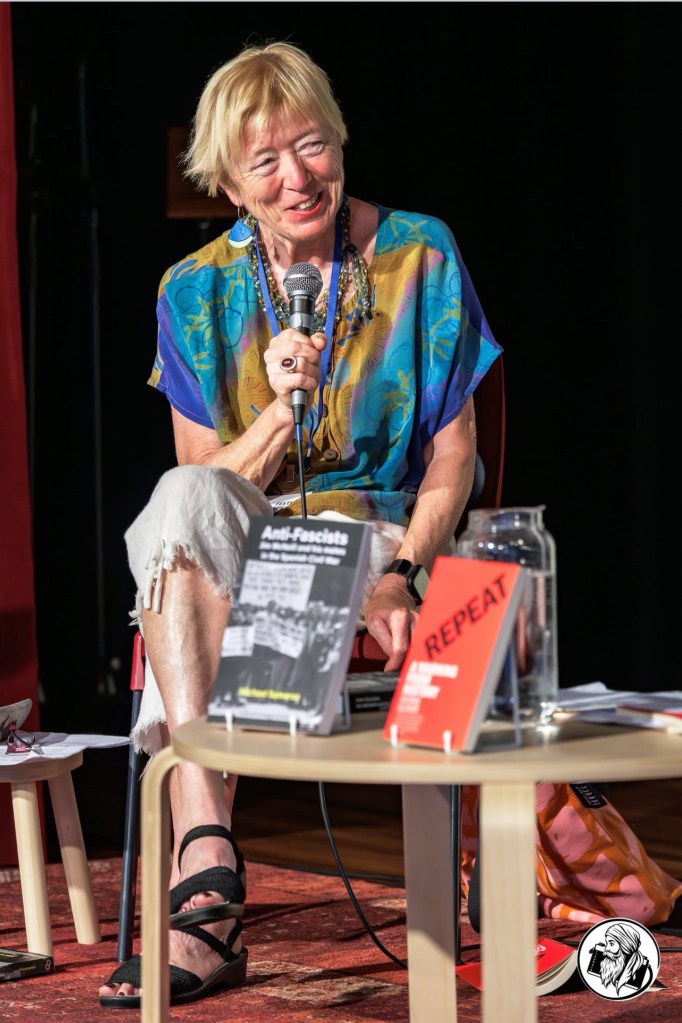

I moderated another hard-hitting panel, on The F-Word: Fascism. Author Michael Samaras told the inspiring story of local ironworker Jim McNeill, a Communist who joined the International Brigade of the Spanish Civil War to help fight fascism. Remarkably, after Stalin sided with the Nazis at the start of WW2, McNeill defied the Australian Communist Party’s whitewash and signed up yet again – with the Australian Army, against Stalin, and Fascism. Dennis Glover’s book Repeat! traced the shockingly similar rise of authoritarianism in 1930s Europe and now, via the actions of Trump, Putin and other autocrats. Despite the dark themes, we learned a lot and had a few laughs as well.

Moderating panel at True Story Festival. Photo: Matt Houston.

DUBLIN

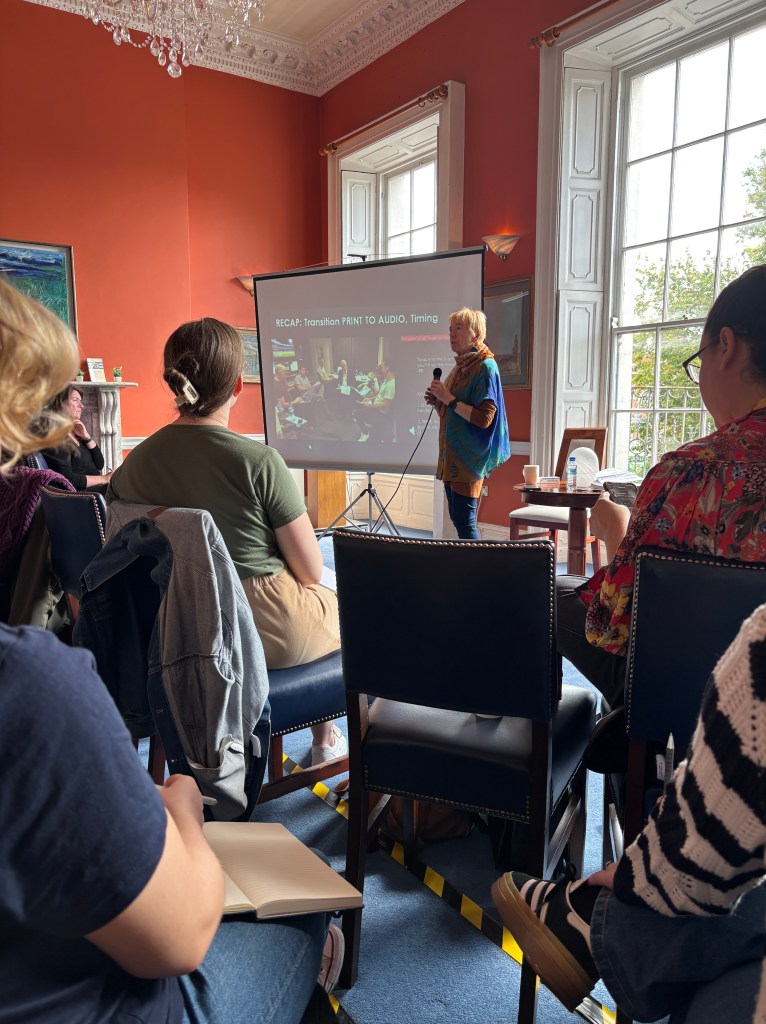

Earlier, I had the lovely experience of running a narrative podcast masterclass at the Irish Writers Centre in Parnell Square, Dublin – literally a stone’s throw from where I was born, in the Rotunda Hospital! It was wonderful to touch base with Irish storytellers at last. I’ve run these workshops all over the world, hearing about projects in Vietnam, China, Europe and America, but never before in my home town.

I was born a stone’s throw from the Irish Writers Centre, Parnell Square, Dublin.

On that same trip to Dublin, I fitted in a seminar at Dublin City University on Podcasts and Life Writing, and a bracing dip in the famous Forty Foot at Sandycove, where Ulysses opens. My swimming companion was none other than the wonderful Dearbhla Walsh, old mate from The Irish Empire doco days, and now the celebrated director of Bad Sisters (Apple TV) – which sees the siblings have ritual dips at the 40 Foot, just as we did!

With Dearbhla Walsh at the Forty-Foot, Sandycove, Dublin, Sept 2025. Water a handy 16!

On then to Krakow, a beautiful, friendly city with a Paris vibe. Gave a paper at the International Oral History Conference on navigating ethics, trust and trauma in our hit podcast,The Greatest Menace. It was well attended and sparked a lively discussion. Overall, though, I was disappointed with the lack of AUDIO (or even video) in the presentations – the ORALITY of oral history is ironically often overlooked. It was good though to meet Mary Marshall Clark and Amy Starecheski from the famed Columbia University Oral History Program, along with the vibrant folk running the London-based pan-Arabic storytelling project (including a well crafted narrative podcast), Tarikhi.

POLAND

After that, sightseeing in Poland, a place steeped in history and culture, with fabulous food, beautiful landscapes and cities pulsing with energy and life (apart from Torun, destroyed by the tourist hordes attracted by its UNESCO listing, the locals seeming listless and constipated).

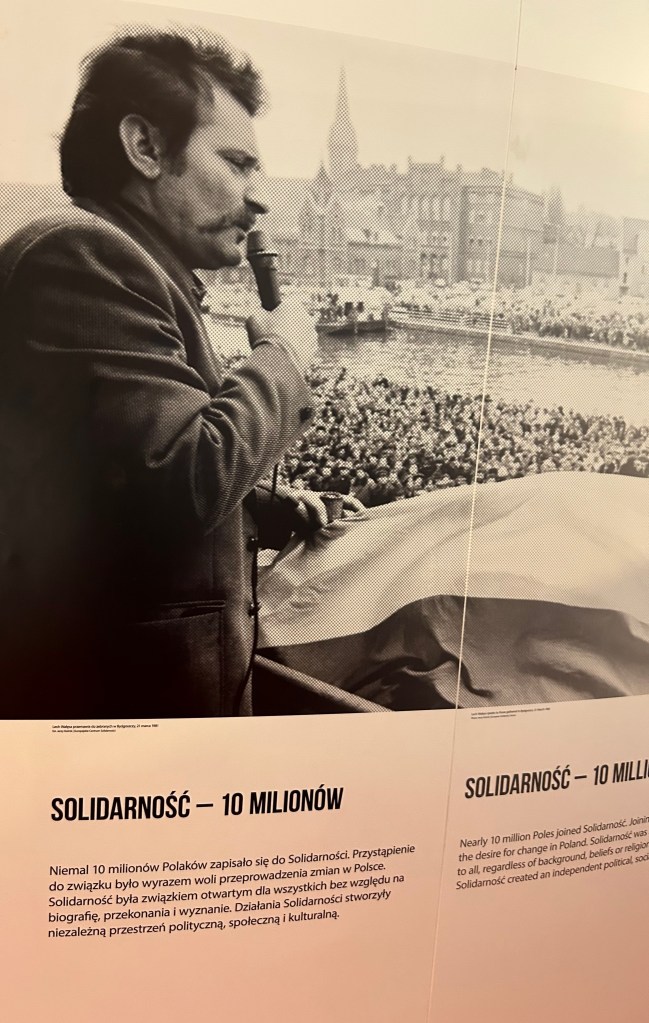

We loved Wroclaw, with its canals and universities; Warsaw, with its painstakingly reconstructed old town; and Gdansk, where a small tour in a flat-bottomed barge recounted the colourful history of this Baltic coastal city, where WW2 virtually started and where Lech Walesa’s Solidarity movement in the 1980s gained a staggering TEN MILLION members and spelled the death of Communism.

It was a thrill to visit the very shipyard where Walesa took his stand, now the Solidarity Museum. I remember him as an absolute hero, but to my surprise, his name does not mean much to thirty-somethings in Australia today.

The museum showing the artist who devised the brilliantly conceived name, Solidarność/Solidarity, for the astonishingly audacious movement that would bring down Communism.

BEST PODCASTS of 2025

Back home, the year ended with my traditional Pick of Podcasts for 2025 for The Conversation. They ranged from audio biographies (Jad Abumrad’s soaring portrait of Nigerian Afrobeat artist and activist Fela Kuti, Guardian Australia‘s compelling account of Gina Rinehart, Australia’s richest woman, called simply Gina) to a deep dive into the French spies who shockingly blew up a Greenpeace boat in New Zealand in 1985 (Fall Out: Spies on Norfolk Island), a whimsical family story linked to unexpected repercussions of the Holocaust (Half Life – The History Podcast), a chilling account of coercive control by a man who admits burning the bodies of two campers in the Australian Snowy Mountains (Huntsman), the return of the sublime storytelling of Heavyweight and much more.

And so ends 2025. Over the break I’ll be prepping my keynote address to MECSSA, a UK media and communications research association, on World Radio Day (Feb 13th), on the topic “Viva The Narrative Podcast: The Case Against Video”. It will be online and in situ 9.30am in UK, so please join us! This article outlines aspects of the debate – including a perceptive observation by Eleanor McDowall, a UK audio creative whose work is always worth listening to and whose generous mentoring of emerging producers along with co-director Alan Hall at Falling Tree Productions is something audiophiles everywhere can give thanks for.

“The absence of images from radio and podcasting isn’t some failure of technology. These audio mediums have grown from a deep love of sound and its imaginative possibilities. When I hear people say the future of audio is essentially television, it makes me feel they never knew what was exciting about sound in the first place.”

– Eleanor McDowall

Time now for a swim – and no, I do not listen to podcasts underwater. Some things are sacred!

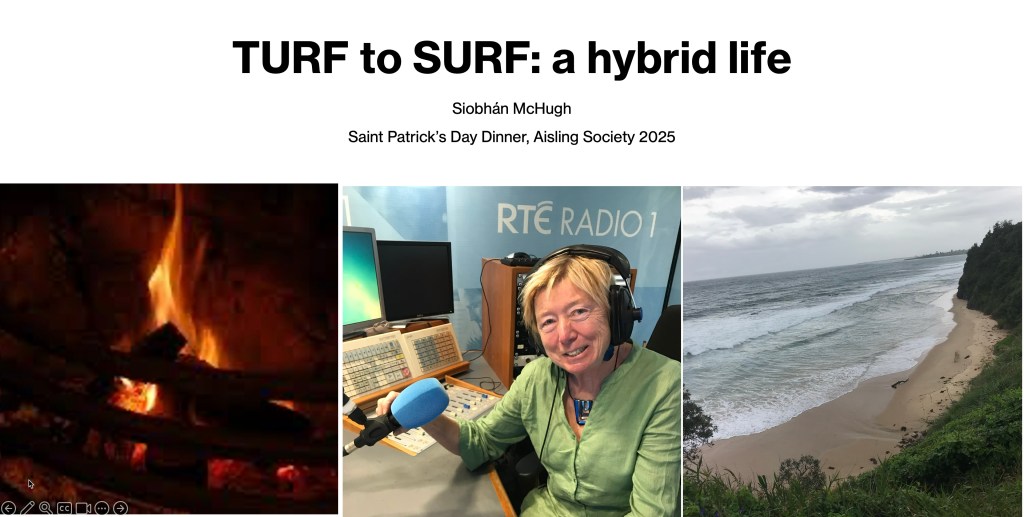

March 2025 marks 40 years since I left Ireland and became an accidental migrant to Australia.

I was honoured to be the speaker at the annual Saint Patrick’s Day Dinner of the Aisling Society, a group formed 70 years ago in Sydney to nurture cultural and historical aspects of the Irish-Australian tradition. It was a perfect opportunity to reflect on the major societal changes I’ve witnessed in that time, in both countries. I reproduce my talk below (I’ve linked to archival audio clips I used.)

It’s an honour to be asked to address you, almost 40 years to the day since I first set foot in Australia. I’ll be referring to three main themes today:

- the changing situation in Northern Ireland

- the altered state of the Catholic Church

- experiences of Indigenous Australians

and how these vexed topics have intersected with my own life as, now, an Irish-Australian.

I came here on what was meant to be a nine-month exchange between RTE and ABC Radio. I vividly remember getting the bus from the airport into Central, marvelling at how carefree the people heading to work seemed, in their light shirts and dresses. All the way in, I couldn’t take my eyes off the bus driver’s legs! I’d never seen a man in uniform wearing shorts before. Authority needed to be fully dressed at home.

At Central, I rang the only number I had in Sydney: Brendan Frost, an Irish sound engineer at the ABC.

Brendan’s wife told me he was already at work, on an outside broadcast with the Sydney Symphony, and to go straight there. Disbelievingly, I caught a cab – to the Sydney Opera House. At security, I expected to be stopped, but at the mention of Brendan’s name I was waved through. After listening to the orchestra in that awe-inspiring setting, it was time for a break. Brendan and his producer cracked a bottle of champagne in my honour.

That glowing bright morning, gazing through the glass at the rippling harbour, something inside me knew I wouldn’t be going back anytime soon.

The Ireland I left in 1985 was a miserable place. It wasn’t the grayness or the eternal rain – I’d had a year of that in Galway and still had a wild and wonderful time, pressed into service as secretary of the very first Galway Arts Festival, surrounded by music, madness, painters and poets. But in 1980 I joined RTE to train for my first REAL job – a producer on RTE Radio One. Ridiculously soon, I was producing the household names of national radio – Mike Murphy, Marian Finucane, Liam Nolan. My very first gig as a reporter was for the legendary Gay Byrne Show.

Just two years in, I was producing Morning Ireland, a breakfast show with astonishing reach in an era before commercial radio competed. A referendum had been announced, proposing an amendment to the Constitution to make abortion more illegal than it already was. The 1983 Amendment split families more than anything since the Civil War, 60 years before.

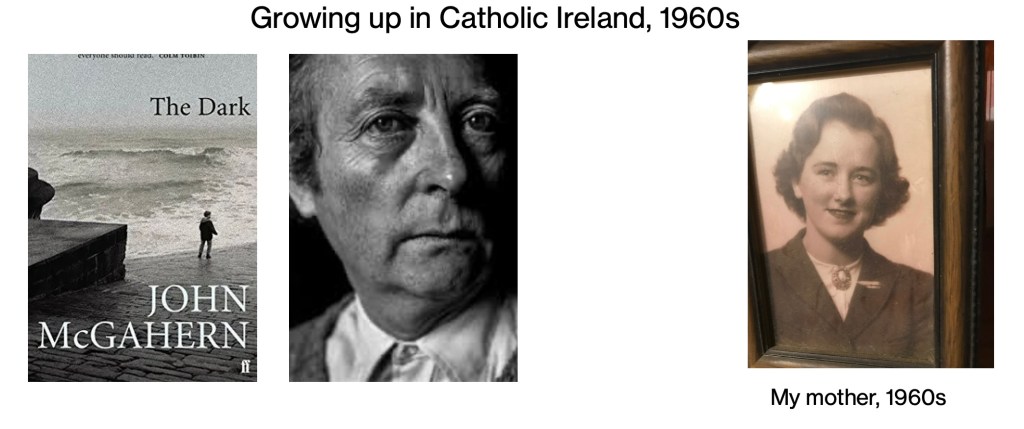

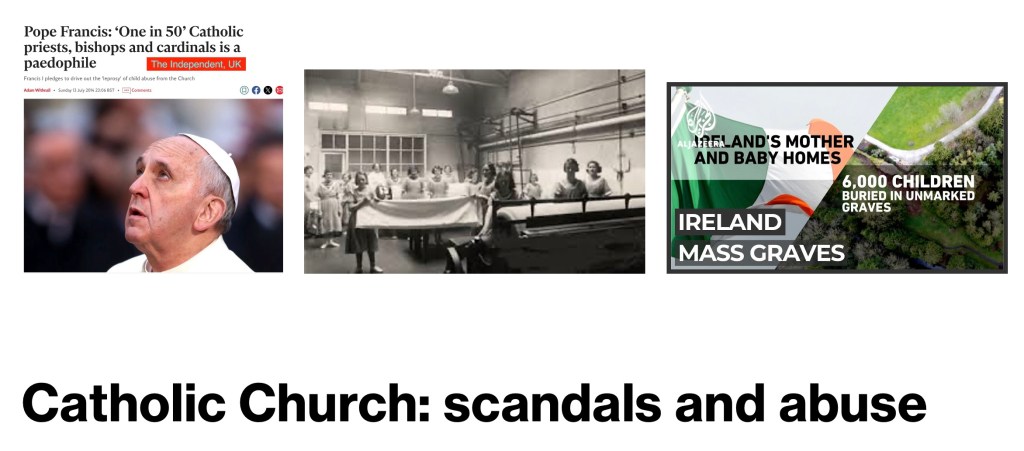

This was a time when, simply put, the Catholic Church ruled Ireland, hand in glove with the State. As we now know, there was SO much evil on their watch. Child abuse, orphaned and dead babies, women mouldering away in the Magdalene laundries. Outside, there was tacit approval of domestic violence within marriage and the exalted role of men, at work, in the home. No divorce, no contraception.

Some of our writers called it out: John McGahern, banned, his novel, The Dark, hidden in my mother’s wardrobe. And I should say here that while I would go on to loathe the abuses of power wielded by the Church hierarchy, I’ve managed to retain affection for some of the cultural rituals that formed what John McGahern beautifully described as the ‘sacred weather’ of a Catholic childhood.

Fintan O’Toole captures the era brilliantly in his memoir, We Don’t Know Ourselves. In 1958 Archbishop John McQuaid prevailed upon the Dublin Theatre Festival to drop a proposed adaptation of Joyce’s Ulysses from the program. They’d already dropped Sean O’Casey. Beckett withdrew his own work in protest. In the end the entire Festival was abandoned.

It was against this historical backdrop of censorship by the Catholic Church that I invited Anne Connolly, Director of a women’s health centre, the Wellwoman, to come on our Breakfast Show. The interview was fairly innocuous – presenter Marian Finucane stuck to the rules about not discussing controversial issues such as the coming Amendment because we were an entertainment, not a news, format.

But by lunchtime, I’d been suspended. Apparently someone from a powerful Catholic lay group rang the higher ups at RTE, to have me removed.

Little did they know what a favour they did me.

Twiddling my thumbs, I got interested in a forthcoming conference on Australia and Ireland, even becoming the honorary secretary. It was held at Kilkenny Castle and opened by a smart, sassy woman with a glint in her eye and steel in her voice. To me, she was a revelation. I decided there and then I wanted to go where the people in power were like her – not the men who ran the show at home.

Susan Ryan was a prominent figure in the Hawke government and chief architect of the world first Sex Discrimination Bill of 1984. She was also a lifelong supporter of Irish-Australian culture, as I was happy to find over subsequent years here. I’m delighted to see they commissioned a sculpture of her last year in the Rose Garden at Parliament House. I think Susan would enjoy this next chapter of my life, where past and present intersected in an unforeseen way.

Fast forward 30 years.

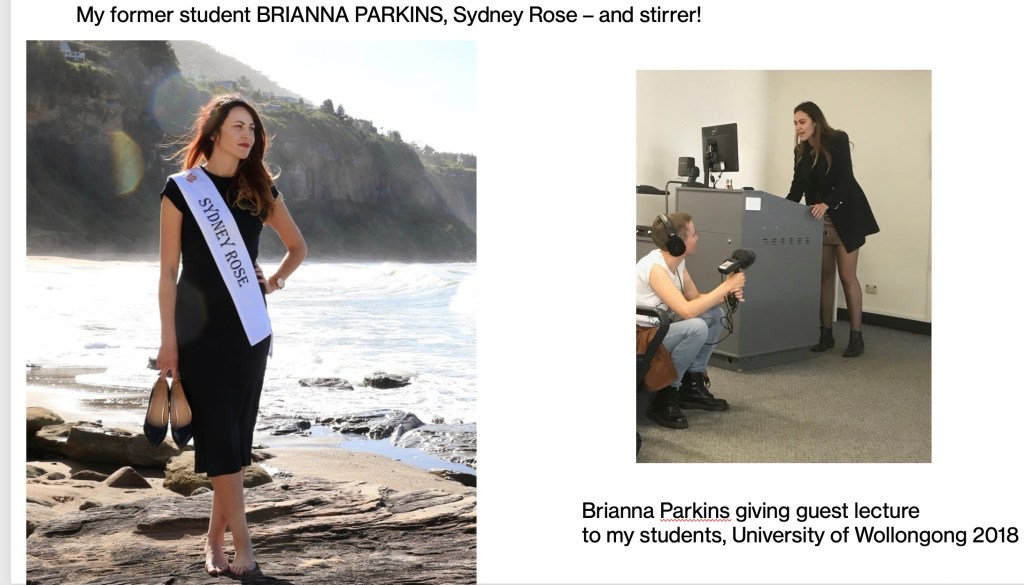

I’m teaching Journalism at the University of Wollongong, where I have a promising student called Brianna Parkins. Bri and I bonded in a kind of tough love way over journalism, feminism and Irishness. She was edgy and fun – and pretty radical.

So imagine my surprise when I saw her wearing a kind of Beauty Queen sash for a photo shoot event. She’d been selected as the Sydney Rose of Tralee. It made sense later – her grandparents hadn’t been back since they left the Liberties in Dublin 50 years earlier and couldn’t afford the fare. As the Rose, she got to bring them home before they died.

But while she was in Ireland, Bri caused controversy by getting embroiled in the budding campaign to Repeal the 8th Amendment – the Amendment against abortion that had been carried in 1983, the one that saw me thrown under a bus.

I told this circular story to Eleanor McDowall, a UK audio producer I met at a conference. Within weeks, she’d travelled to Australia to interview me and Bri for a radio documentary for BBC. Bri was coincidentally doing a guest lecture for my students that day.

The resulting documentary, A Sense of Quietness, has four female voices – Bri, me, Anne Connolly and an anonymous Irishwoman who’d recently gone to the UK for an abortion. It’s a marvel of concision and has won many accolades. Here’s Bri recounting how she livened up the usually bland proceedings of the Rose of Tralee Festival as it was broadcast LIVE on RTE – a huge television event, a bit like Eurovision.

SO MUCH HAS CHANGED in those four decades since I left. The Catholic Church is now on its knees, ordinary Catholics disgusted by the abuse, cruelty and scandals.

But weirdly, in Australia, despite describing myself on arrival as a refugee from the Irish Catholic Church, I was taking a different direction – towards, instead of away from, my culturally Catholic identity.

Because in Australia, I discovered, to be Irish WAS to be Catholic, whether you liked it or not. It didn’t seem to matter that as we know, a good 20% of Irish immigrants to Australia were Protestant of one kind or other. ‘Religion’ was code for politics: here, Irish meant Catholic and Protestant meant some variation of British.

I gradually learned the troubled history of the Irish as a maligned underclass in Australia. Sectarianism was evident from the earliest convict days, as Jeff Kildea and others have documented.

By the early 2000s, Australian demographics had shifted. Working at SBS with people of many ethnic backgrounds, I realised with dismay that to a Vietnamese or Indian Australian, this was all irrelevant – Irish and British were just lumped together in their minds as ‘White Australia’.

History retrofitted: Irish now lumped together with British as a mythical monolith called White/Settler Australia

Shocked by this retro-fitting of history, and the glossing over of colonial injustices perpetrated not once but TWICE on us, I researched the discrimination suffered by Irish Catholics for my doctorate.

I recorded oral histories with people at the heart of that bigotry: those involved in what most folk here will have called Mixed Marriages – a Catholic marrying a Protestant. They’re woven into a short series called Marrying Out. I’ll play just one clip here to illustrate, of Julia O’Brien and Errol White, who eloped to Sydney from Maitland in the 1940s. Their daughter, Susan Timmins, describes the enduring feud that followed.

Susan died not long ago, with Parkinsons, and her husband Peter followed last year. It’s such a loss, because people still need to hear this history. Only weeks ago I was judging podcast awards and one entry was an SBS series called Australia Fair, on Australia’s immigration history. It’s very good at recounting awful racism towards the Chinese, Pacific Islanders, postwar Europeans and more. Except for one stunning misrepresentation – the Irish are thrown in along with the Brits as part of some assumed monolith called White/Settler Australia.

But things HAVE of course changed hugely, for Irish-Australians, over the last 40 years. We certainly are now part of the Establishment, something that would likely make Robert Menzies turn in his grave. And as such, you’d hope we’d support those lower down the ladder, the latest wave of refugees and immigrants.

Not to mention Indigenous Australians.

I believe the Irish have a special affinity with Aboriginal Australians. It’s not just that we were co-colonised, through there IS that. It’s that we share a deep attachment to the land and its stories. I love the anecdote about the Aboriginal-Irish singer Kev Carmody, who was playing at a festival in I think Donegal. He went out early to check out the venue, a field in the middle of nowhere. A nosy farmer wandered over and pointed out a circular mound he called a Fairy Fort. Do you believe in Fairies, Kev asked. I do not, the farmer said indignantly. And after a minute: ‘but they’re there!’

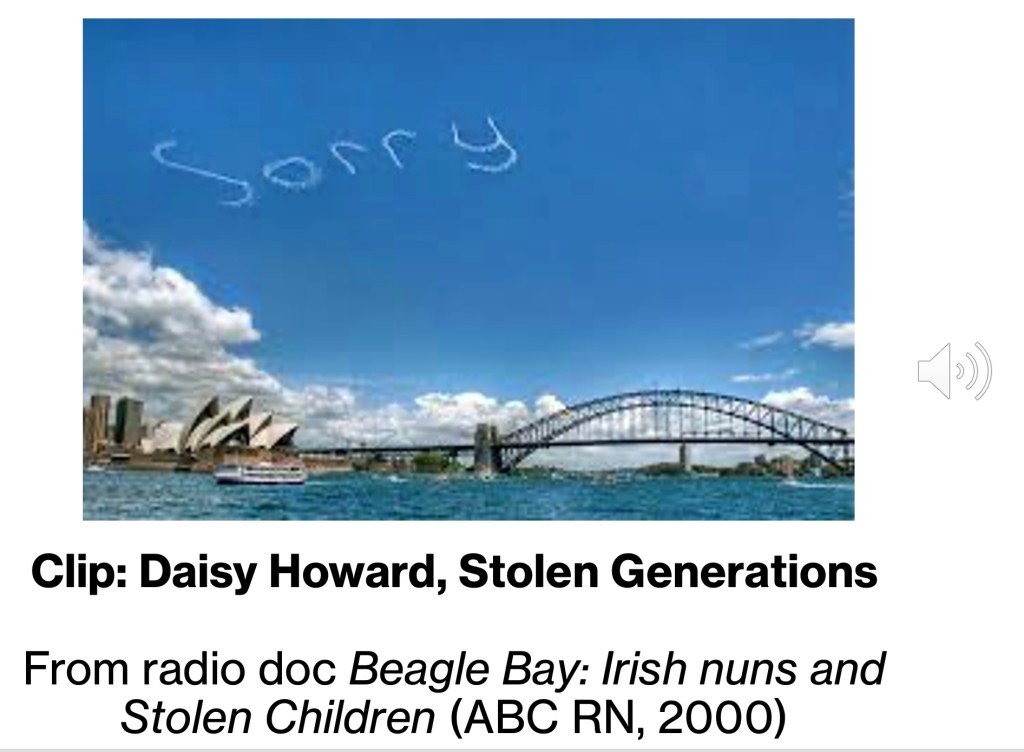

I’ve been lucky enough to have gathered oral histories of Aboriginal Australians from artists in Arnhem Land to members of the Stolen Generations. One documentary I made is called: Beagle Bay, Irish nuns and Stolen Children. It tells the stories of several Aboriginal women, removed from their families as toddlers by government edict and raised by a branch of John of God nuns established by a County Clare sisterhood at Beagle Bay near Broome in 1908.

I arrived there in 2000, bristling with righteous rage – how dare these religious institutions kidnap and indoctrinate these kids. To my surprise, the Aboriginal women told me they loved the nuns who ‘grew them up’. Yes, they were devastated to have lost contact with their family and culture. But they refused to condemn the nuns themselves. Later I’d understand that the nuns and girls had bonded in solidarity against the sexist dispensations of the Church. Here’s a clip from one of those women, Daisy Howard, recalling her mixed feelings about her experiences.

I played clips of these Aboriginal women in Ireland, at a public lecture at University College Galway and at Pavee Point, an educational centre for Travellers (the marginalised group we used to call itinerants). As Daisy, from Halls Creek in the desert of Central Australia, described her conflicted feelings about her childhood, distance and difference didn’t matter. The Traveller women nodded and cried. That empathy was just as evident at Harvard, where I played the clips to a seminar at the Native American centre.

It taught me the universality of human suffering. The details about oppressor and oppressed change, but the lived experience is the same, just in different contexts.

Which brings me to Northern Ireland.

In my lifetime, N Ireland has moved through the civil rights movement of the late ‘60s to the era of occupying British forces, prolonged internment of men without trial and in the ‘70s and ‘80s, a terrible all out blitz of bombs and bullets and the horror and tragedy of the hunger strikes in 1981, when Bobby Sands and nine others died. British PM Margaret Thatcher remained intransigent, refusing to call them political prisoners. But public opinion changed, as it had back in 1916, when other Irish Republicans had died as martyrs. Over 3500 people would die before the historic Good Friday Peace Agreement of 1998.

What a moment.

In 2000, I went back to live in Ireland for a year so my two young sons could get a sense of the culture and get to know their numerous relatives. While there, I heard that Patrick Dodson, the senior Indigenous senator, was on a factfinding tour. I’d met Pat at home in Broome and he agreed to let me make a documentary about his trip.

He’d already been to Belfast to meet political activists on both sides. Once, he told me, he was in the office of David Ervine, a notorious former Loyalist paramilitary who was now a law-abiding politician. They were waiting for the Sinn Fein rep, who was late. Ervine called him and said: ‘Get down here and meet someone who claims to be even more oppressed than you are!’

Pat loved that black humour. I’ll come back to him and N Ireland later.

Overall – despite the chaos of the current world order and the travesty of having convicted rapist Conor McGregor as the VIP Irish guest in the White House for this recent St Patricks Day – I see positive changes in the last 40 years.

One, the demise of the Catholic Church’s untramelled power.

We may actually see a United Ireland

Two, we may actually see a United Ireland. If we do, its citizens will have to figure out how to live with a new pluralism – not just of Protestant Loyalists and Catholic Nationalists, but with the 9% of the population now born overseas, immigrants and refugees from all over the world.

My very first radio documentary for RTE in 1981, called In a Strange Land looked at the few thousand IMMIGRANTS then in Ireland. I was curious how they felt about being NOT part of the culturally almost homogenous Republic. They were mostly muddling through – not encountering prejudice so much as bewilderment. One African student told me how the children would run up and smear chalk on his arm, to see if it would turn black. He took no offence. It was born out of innocent curiosity, not hate.

Now, like the rest of the world and perhaps because it was unprepared for the infrastructure and support services these newcomers would need, Ireland has a strong anti-immigrant movement.

It has many obstacles to face: economic, social and political.

But how are my siblings and friends and their families faring compared to when I left in March 1985? They’re a thousand times better off. My best friend at the time ended up as a single mother in council housing, but she was able to buy it out and can afford the occasional RyanAir holiday in Europe to escape the weather. Her son is highly educated, a teacher himself now. EU laws ensure decent health and social services, not to mention unrestricted career options across Europe.

Ireland, of course, shares with this country pressing social problems such as violence against women, huge and growing inequality and a housing problem that seems as bad as our own here in Sydney.

But I’m not going to end on a pessimistic note. Like so many, I found opportunity here, a chance to follow your dream. I was so energised by the openness of this country, its willingness to take you as you were and give you the famed fair go, that I never wanted to return to the land of Who You Know that was Ireland.

By great good luck, a year after I arrived I was invited to research the history of the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Scheme, a nationbuilding project that was the de facto start of multicultural Australia. It would become my first book.

My Sidney Nolan Moment – but I missed it!

This slide shows the Dublin launch, at another Australia-Ireland conference in 1989. The man holding my book is the then Australian Ambassador to Ireland, Brian Bourke – who’d later be disgraced over corruption issues in WA. The man in the hat is Con Howard, the colourful former Irish consul in the US who somehow managed to pull together that first conference in 1983. And the man on the right… some of you might recognise him. I first met him just before the Kilkenny conference. Con was always hosting visiting Australians and I got roped into one of these long lunches. My job was simply to charm the visitor. But this man didn’t say much and I ran out of jokes. Groping to remember what his angle on Ireland was, I said, ‘I believe you paint?’ He smiled slightly. Yes. He did. I told him he should visit the West so, where the light was wonderful. It was only when I got to Kilkenny Castle and saw the magnificent Burke and Wills exhibition that I remembered his name: Sidney Nolan.

Amazingly, my book, The Snowy, won the NSW State Literary Award for Non-Fiction, which carried a prize of $15,000. As a freelance documentary maker I was then a virtual pauper. It miraculously became a deposit on my first home.

The Irish are no different from other migrants in that we all leave home in search of that simple yet elusive concept, A Better Life. Australia has given me that, in spades. I’m grateful to the generous people who guided me as a raw arrival, helped me see the beauty and complexity of this vast continent.

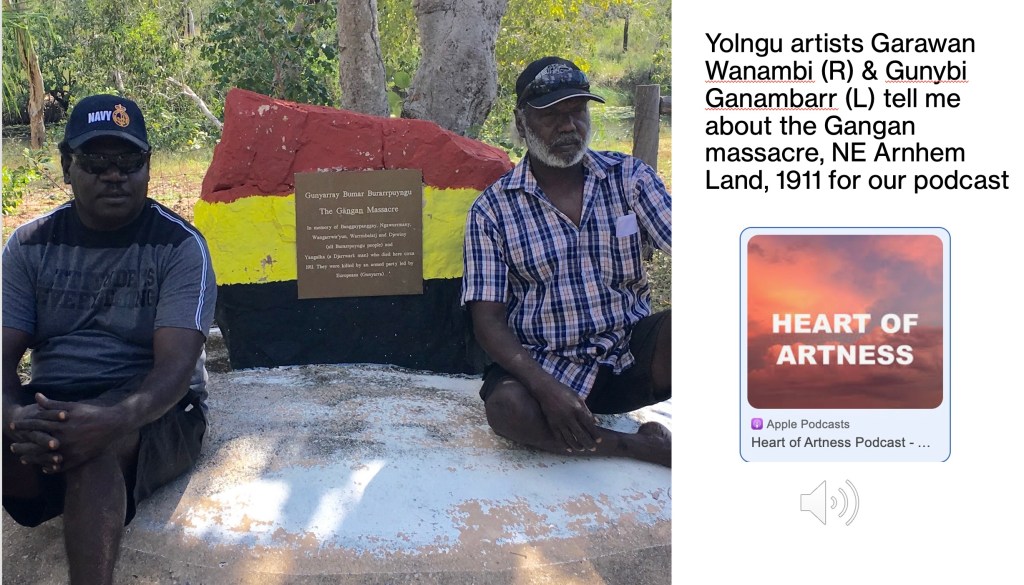

Ten years ago, I was invited to be part of an academic research project into the crosscultural relationships behind the production of Aboriginal art. It’s very important, culturally and economically, especially in remote communities. But little was known about the collaborative process between the black artists and largely white managers who ran the art centres. One centre we studied was at the Yolngu community at Yirrkala in NE Arnhem Land. I recorded oral histories there and compiled them as a podcast, Heart of Artness.

One of the most special moments in that project was when we were invited to a small community at a place called Gangan. The drive was 3 hours on a dirt road and the elder artist, Garawan, travelled with us. I ran out of small talk, and for some reason, looking at the ancient landscape, the stories of my youth came back to me. I told Garawan the Irish legend of the Salmon of Knowledge, my favourite. He listened quietly, then told me he ‘knew that story’. When we got to a waterhole near his home, he told me his water goanna lived there, ‘like your salmon’. It somehow created a bond, and Garawan must have decided to entrust me then with his own story – a dark one, about a massacre. It happened in 1911, by the river. Garawan, another brilliant artist, Gunybi, and a young ranger, Yinimala, also an artist, took me to the location.

I’ll play you a short clip – it opens with them speaking their language, Yolngu Matha. (Full analysis of that research project here, for anyone interested.)

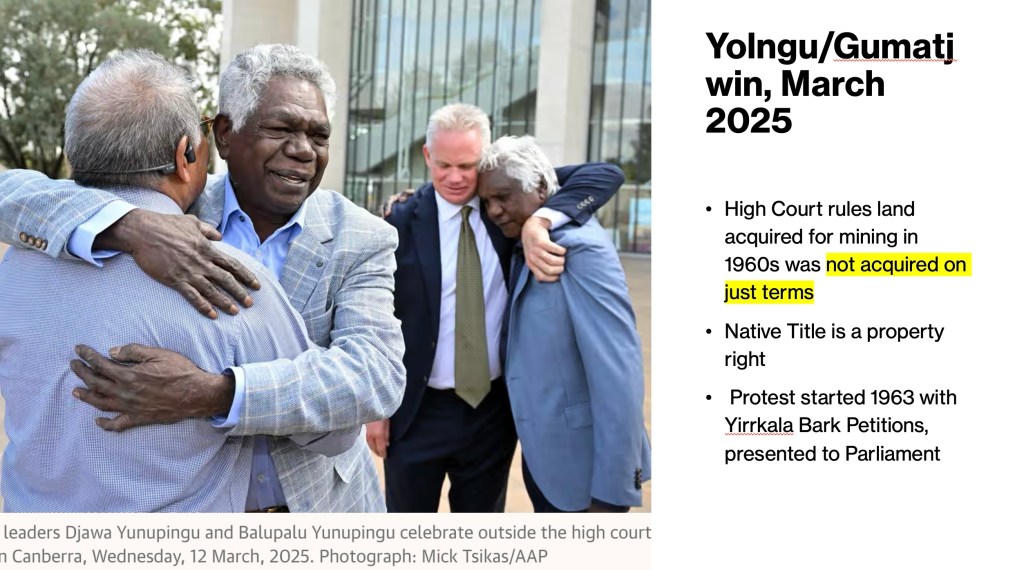

The country we drove through belonged to the Yunipingu family of the Gumatj clan – a famous family, known for the band Yothu Yindu and more. In 2019 the late Dr Yunipingu launched a Native Title case against encroachments by bauxite mines dating back to the ‘60s. In fact the Yolngu had protested the mines as far back as 1963, via two extraordinary bark petitions presented to Parliament in Canberra. Dr Yunipingu died two years ago. But just LAST WEEK, his brothers won a huge victory in the High Court on his behalf. It ruled that the Yolngu land had not been acquired ON JUST TERMS and that the community was owed substantial compensation. It’s as big a legal win as Mabo or Wik.

So I’m glad to be ending on a positive note – despite the bleak results of the Voice Referendum.

I’ll leave you with some thoughts on N Ireland, and words from someone far wiser than me.

From those first tentative years of peace, the situation has stabilised. We currently have a N Ireland First Minister from a post-conflict Sinn Fein background, Michelle O Neill.

Two significant points:

- Catholics now outnumber Protestants. The statelet was deliberately carved up so as to give Unionists a 2:1 majority. But the old taunt of Catholics breeding like rabbits has proved prescient.

- The 1998 Agreement allows that a referendum can be held on a United Ireland if a majority North and South wish.

That referendum seems increasingly likely. Several credible pundits think it may happen in the next 10 years.

I ended up back at the Sydney Opera House not too long ago, or at least observing it from the Museum of Contemporary Art, where I was interviewing Indigenous artist Richard Bell for our podcast, Heart of Artness. Richard has lost much of his culture and language. He gets his revenge on the coloniser by having them buy his art, in which he enunciates and excoriates their crimes. He’s gone from being a self-described derro in Redfern to the toast of the Tate.

As the Father of Reconciliation, Pat Dodson has had no happy ending. But he has the enduring satisfaction of knowing he fought the good fight, and he gave his all. He and others have laid the ground. I think we’ve all seen a hugely increased awareness across the country of the Indigenous presence – which when I came here, was so often invisible or ignored.

I want to end with a session I recorded outside Dublin around Christmas 2000, where Pat was the keynote speaker at a kind of Youth Retreat for Reconciliation funded by the EU to break down prejudice and bigotry of all kinds. There were high school kids there from north and south Ireland, Catholic and Protestant, and from the UK. After a day of workshops and talks by community leaders, one boy asked a question with the crystal clear innocence of youth: what was the solution to get a United Ireland.

The reply came from Matt, a self-described former Unionist heavy, now a youth worker for peace. Here’s his answer.

CLIP: MATT (1.17) (from Reconciliation, from Broome to Belfast, ABC 2001)

The next question came from a girl who described herself as a Pakistani Muslim from Birmingham. I’ll end with Pat Dodson’s response to her.

25 years on, it still sends shivers down my spine.

CLIP: PAT DODSON (from Reconciliation, from Broome to Belfast, ABC 2001)

Go raibh míle maith agaibh. (Thank you)

Thanks to Jeff Kildea, Mary Barthelemy and all at the Aisling Society and to Rosie Keane, Consul General, Consulate of Ireland, Sydney.

2024 was a BIG year. On June 6, The Greatest Menace team attended state parliament in Sydney as guests of the Premier of New South Wales, Chris Minns, as he formally apologised to the LGBTQIA+ community for injustices suffered before homosexuality was decriminalised in 1984. The apology was partly triggered by our podcast. Pat, Simon, and I listened along with TGM contributors Jacquie Grant, a trans woman and former inmate of Cooma Prison, and gay couple of 55 years Terry Goulden and John Greenway, as politicians of all stripes spoke of their regret at the demonisation visited on the LGBTQIA+ community until 1984.

Outside Parliament House, Sydney, 6 June 2024, before the apology. From left, Terry Goulden and his husband John Greenway; Paul Horan, executive producer, Audible; Jacquie Grant; Simon Cunich; Pat Abboud, beckoning to Siobhán McHugh to join the photo rather than take it.

I wrote an in-depth article that analyses the making of the podcast: ‘Intimacy, Trust, and Justice on The Greatest Menace, a Podcast Exposing a “Gay Prison”.’ It’s published in the open access journal Media and Communication – download free pdf HERE.

Podcast Studies Roundtable, IAMCR 2024, Brisbane

Also in June, I co-convened, with Prof Mia Lindgren, the first ever Podcast Studies preconference event at the IAMCR (International Association of Media and Communications Research) conference. Organised with help from fellow pod scholars Dr Dylan Bird and Lea Redfern, it was a wonderful sharing and celebration of academic podcast research. We deliberately kept the event small and intimate, the 18 scholars from four continents forming a proto Podcast Think Tank that we hope will continue to develop research networks and collaborations – see the full report on proceedings.

Pod scholars from China, India, the US, Africa and Australia letting loose after an intense, rewarding – and fun! – day.

HEART of ARTNESS – Season 2

Back home in early July to another intimate podcast gathering: the reconvening of the team from Heart of Artness. We used the excellent Rodecaster kit to record a stimulating chat in my lounge room that will (one day!) kick off a second season. It will incorporate interviews I did a while back now with Indigenous artists such as Archie Moore, whose breathtaking work, Kith and Kin, won the Golden Lion award at the Venice Biennale in April 2024 – the highest global accolade. Archie was already meditating in our interview on the ruptures wrought by colonisation which he explores in his Biennale installation.

Team from Heart of Artness podcast preparing for S2: Guy Freer, technical producer; Ian McLean, art historian; me and Margo Neale, co-hosts.

Filmed interviews & lectures from Sydney to Madrid

In September, I was pleased to give a series of guest lectures on everything from podcast aesthetics to ethics, to media/sound students at Macquarie University, where I am Honorary Associate Professor in the Dept of Media, Communications, Creative Arts, Language, and Literature. I’m also a member of their dynamic Creative Documentary Research Centre. So I was delighted to be interviewed for the CDRC by colleague Dr Helen Wolfenden, on all manner of podcast-related themes, from practice to pedagogy. The full interview is online here, usefully subdivided into chapters – handy for teaching perhaps.

The short clip below has me reflecting on whether narrative podcasts are art or journalism. It was clipped by Florence Lumsden, an indie podcaster based in North Carolina, whose show The Format delves into the podcast industry – my interview with Flo will be up early in 2025.

Which reminds me: I did a loong and satisfying interview with Spanish journalist Gorka Zumeta on all things podcasting following my residency in Madrid at Universidad CEU San Pablo in late 2023, kindly hosted by Dr José María Legorburu. Gorka probed deeply into the philosophy of sound and the business of audio/podcast journalism – it’s published in both Spanish and English, here.

Being introduced at CEU San Pablo against a life-size image of my book!

ORAL HISTORY meets PODCASTING

For me, podcasts, radio documentary and oral history are interlinked, as I always turned my big oral history projects into an audio series, and sometimes a book as well. My first book was a social history of the Snowy Scheme, a huge hydroelectric project that became the birthplace of multiculturalism in Australia. I was lucky enough to interview many dozens of those European migrants who made a fresh start here after WW2 by working on it – and what a diverse, polyglot bunch they were. In October, for the 75th anniversary of the scheme’s launch, I got wheeled out again to talk about that remarkable time, when people of over 30 nationalities who’d been fighting each other only a few years before, came together in the rugged Australian Alps to build one of the engineering wonders of the world. Better still, I got to play audio clips from the original oral histories I recorded in 1987/88 – the full collection is archived in the State Library at Sydney.

Speaking at the Engineers Australia event, slide of Snowy workers c. 1951 behind.

It was a delight to speak to 800 engineers (100 in the room and 700 online) to celebrate the scheme. Most were young, many of them migrants themselves, and the culture shock and gradual accommodations between ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Australians of the 1950s and ‘60s resonated. The event was introduced by the extraordinary Arnold Dix, a Snowy boy who grew up by Lake Jindabyne, created by the project. Arnold has several degrees, in geology, law and engineering, and puts them all to good use as head of ITA, the International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association. Over fish and chips afterwards, Arnold told me how he’d supervised the rescue of some 40 Indian miners after a tunnel collapse the year before.

Arnold Dix (R) with Damon Miller, an engineer on Snowy 2.0, a current extension of the original project.

Arnold currently advises the UN and somehow runs a flower farm on the side. The Snowy is still producing great stories, 75 years on! I told several more of them on various ABC shows, including RN’s Late Night Live, where the redoubtable host David Marr rashly invited me to sing. Which is how my impromptu rendition of the old folk ballad, Put a Light in Every Country Window, was unleashed on an unsuspecting public.

In November, it was off to Melbourne for the Oral History Conference of Victoria. I loved meeting the current crop of practitioners and hearing about fascinating projects from interviewing centenarians to mapping Melbourne’s buskers as both a podcast and a PhD. But I was really hanging out to hear the keynote, by my inspiration of so many years, Alessandro Portelli, all the way from Rome. At 82, Sandro was as eloquent and insightful as ever on how we make meaning of our lives, and the stories we tell about them. He truly is the world’s most brilliant oral historian, as his colleague and friend Prof Alistair Thomson introduced him.

Alessandro Portelli delivering the keynote at OHA Victoria Conference, Nov 2024.

I was thrilled – and a bit nervous – when Sandro attended my own session, a masterclass on the making of The Greatest Menace. The format, of converting interviews to serialised storytelling, crafted with archival and ambient sound, was new to him, he told me – but ‘great’. That got me thinking: what if current podcast producers were to get together with Sandro, and ask him to select and discuss works from his archive? What a cracker podcast that would be – because the meaning and impact of oral history only deepens with age and fresh contexts. Later I introduced Sandro to some excellent Italian podcast academics and practitioners… and the excitement was mutual. Watch this space! This is where the fellowship and shared community of audio people is so rewarding.

Honoured to have Alessandro Portelli attend my masterclass – and get interested in podcasts!

MY TOP PODCASTS for 2024

At year’s end, I delivered what has become an annual ritual – to select the year’s best podcasts for The Conversation. It’s always tough to whittle it down to ten, while trying to cover a range of genres and origins. There were obvious ones, such as The New Yorker and In The Dark’s forensic expose of US war crimes in Iraq. But there were also ones that might have flown beneath your radar, such as The Belgrano Diary, a tour de force hosted by the Scottish writer Andrew O’Hagan, laden with poetic, sonorous reconstructions and memorable observation. (‘He looked like he’d been on a lifelong gap year.’).

Some I couldn’t fit in include Trial by Water (revisits the ghastly story of the father who drove his three boys into a dam and adduces compelling new evidence), Cement City (a tender if overlong portrait of a declining US town) and Baghdad Nights (an examination by my old collaborator, Richard Baker – Phoebe’s Fall, The Last Voyage of the Pong Su – of the sordid macho world in which Australian wheat officials associated with the Saddam Hussein regime).

2025 is shaping up to be exciting.

I’m headed to Europe in Sept/Oct, to present at the International Oral History Conference in Krakow. The conference dinner is being held at the Kosciuszko Mound – a memorial to the great Polish freedom fighter, after whom Australia’s highest mountain is named. It’s in the Snowy Mountains, site of my first book. I love these synchronicities!

Meanwhile, it’s high summer here and I’m off to the beach with Godot dog. And yes, he’ll make us wait 😄

Happy New Year!

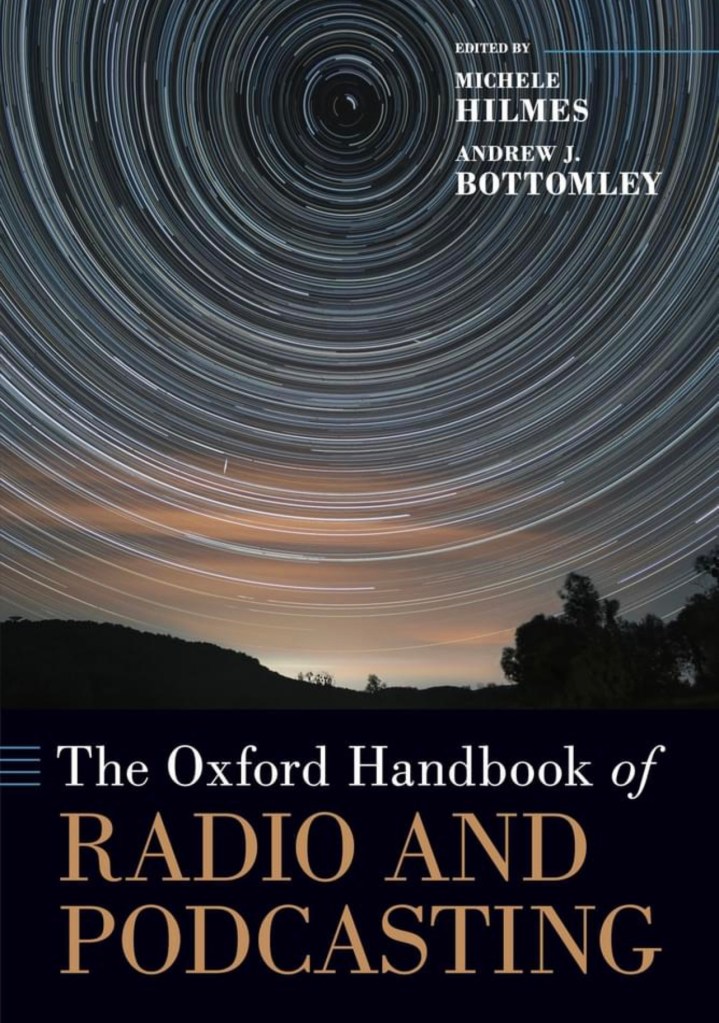

One minute I’m pinching myself, to see if that quote from me on Oprah Daily is real. The next, I’m getting a Google Scholar alert that my chapter, The Invisible Art of Audio Storytelling, has been published in the Oxford Handbook of Radio and Podcasting by Oxford University Press. If ever proof was needed of the power and scope of podcasting, this was it!

The message from Oprah came through as I was holidaying in Sri Lanka. We were staying at the charmingly run down Bandarawela Lodge, still recovering from the rare experience of seeing elephants mating in the wild, when I saw the email: “I’m an editor at Oprah Daily, and I’m working on a story all about the effect of constantly listening to podcasts… is it leading us to be less focused… be afraid of the voice in our own heads? Or is it something that actually curbs loneliness and generates knowledge?”

It was a great question, I told Cassie Hurwitz, one close to my heart. “I’m firmly in the camp that podcasts reduce loneliness and create/share knowledge. Often at the same time, as when you develop a close attachment to a podcast host, your new best friend – feelings of intimacy and trust that are hugely valuable in an age of misinformation. Social media suck you in to mindless scrolling, produce anxiety AND waste screeds of time – but podcasts let you multitask – your imagination takes flight when you’re not harnessed to a screen. And the things you learn!”

After a wonderful two weeks immersed in Sri Lankan history (humans have been there 125,000 years, go figure), its wilderness (I will never forget that elephant couple!) surf beaches, tea plantations and scrumptious spicy food, Cassie and I resumed the conversation in Australia.

PODCASTS are GOOD, I explained, because:

- They create a sense of companionship and empathy… you get to ‘eavesdrop’ on folk (who feel a bit like you) as they laugh and banter about their day, or sometimes deal with heavier stuff, but again in a ‘real’ way that makes you feel for them. It’s like having a new friend to hang out with, but without the hassles and responsibility. e.g Normal Gossip

- You LEARN things, effortlessly, as you drive/do chores/commute. So many fun chatcasts that make you expert in History, or Climate Change, or broader themes like Class in America (Classy) or the beginnings of Fake News (Things Fell Apart), or a Gay Prison in Australia (The Greatest Menace), or crazily niche stuff that only 200 others care about, like my co-hosted podcast about the largely undocumented ways white and black folk work together to produce stunning Aboriginal art in Australia (Heart of Artness).

- You get entertained. At best, by lean-in, addictive storytelling, podcasts that are about PEOPLE and what makes us all human, sometimes through a lens of crime, sometimes through a purely personal take, such as in Million Dollar Lover: is rich 80-something Carol being exploited just for money by her druggie boyfriend Dave, or is there a real spark?

Sure, podcasts too can be harnessed for bad intentions, to spread hate or bigotry. But audio doesn’t seem to suit those folk as well. I listened to Tate Talk to research this question. It’s hosted by Andrew Tate, the ‘celebrity’ former kickboxer charged with rape, sex trafficking women and other offences. He doesn’t ‘get’ audio. In his trailer Andrew Tate – My Principles, he’s shouting (at who we don’t know) and his loud alpha-male persona is sabotaged by schmaltzy orchestral music that undermines his Bro’ tone (bad choice!). There’s no light and shade via timing or phrasing, to let a point sink in. That punctuation stuff matters in audio – it’s what allows us to take in what we’re hearing. (Stand-ups know this – that’s why they’re so good at podcasting). The shoutiness in itself is offputting in audio. We respond MUCH more positively to a human voice that is warm and intimate, not one haranguing us.

Check out Cassie’s story, This is Your Brain on Podcasts. I go into these same ideas in much greater depth in my Oxford chapter, here. In it, I deconstruct the invisible art of audio storytelling aided by illustrative clips from The Saigon Tapes, a non-narrated montage feature by UK producer Alan Hall, and Goodbye To All This, a moving podcast memoir by Australian Sophie Townsend on the death of her husband and its impact on her and their two young daughters. I’m in excellent company – the anthology is a treasure trove of essays and thoughtpieces about audio down the ages.

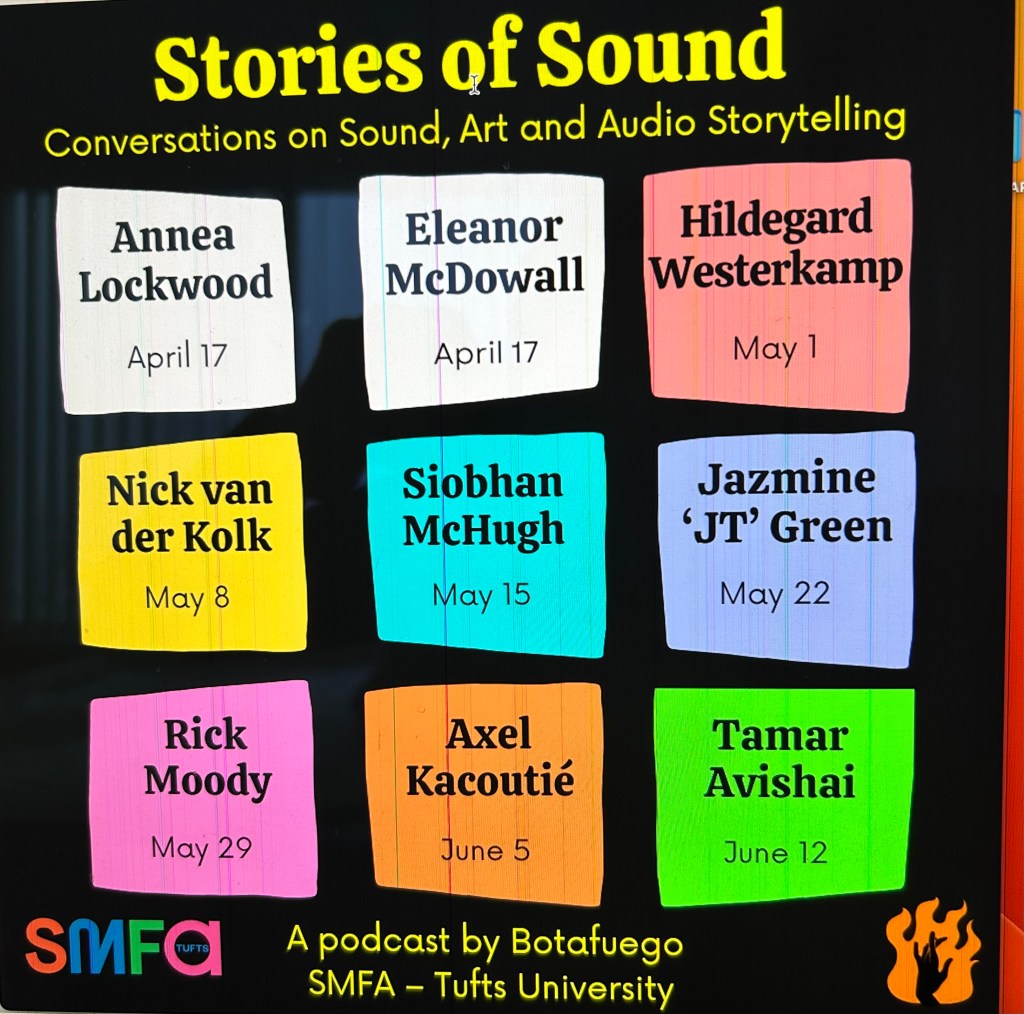

Serendipitously, I had the privilege of delving even further into this arcane art in a meticulously produced podcast, Stories of Sound, by Italian sound artist and academic Riccardo Giacconi, which launched the same month. It features nine sound creatives from across the generations and around the globe, reflecting on their practice.

To be discussing the art of audio in the company of venerable sound artists such as Hildegard Westerkamp, the insightful documentary maker Eleanor McDowall and edgy podcast producers from Nick van der Kolk to Axel Kacoutié is an absolute honour.

In my episode, I get to go from my origins as a fledgling radio producer in Ireland, through what I learned conducting hundreds of oral history interviews across a universe of human experience, then shaping revelatory interview with music, sound and script into coherent, hopefully compelling, narrative podcasts.

From Oprah Winfrey’s massive popular orbit to the intellectual heights of Oxford University to the passionate art of telling stories in sound, all in a month: this is why I believe podcasting can connect with pretty well anyone, anywhere. And we are all the richer for that.

Reclining Buddha in Dambulla Cave, Sri Lanka, a temple that dates back to 1st century BC.

PIC: Siobhan McHugh and Carolina Guerrero, CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios, Lisbon.

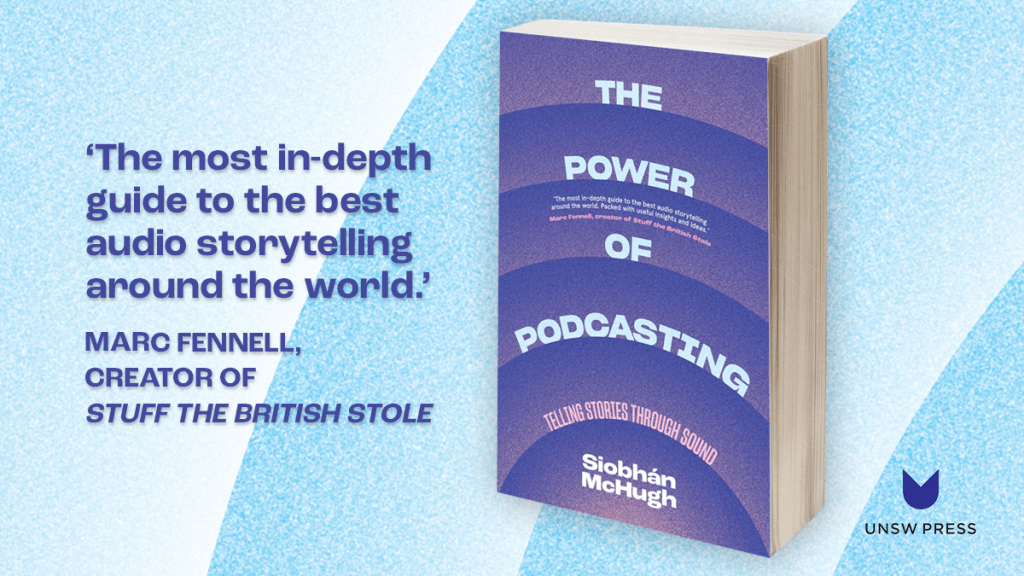

Colombian podcast executive Carolina Guerrero attended a narrative podcast workshop I gave at the Global Editors Media Summit, Lisbon, in 2018 and we found lots to talk about afterwards. I love Carolina’s work at Radio Ambulante, so when my book The Power of Podcasting was coming out in 2022, I asked her to read it and give me a comment for the cover. ‘An invaluable resource for anyone interested in understanding today’s global podcasting phenomenon. I learned so much,’ she generously responded. I’m more used to being reviewer than reviewed, but it got me thinking about being the subject of the review. So I’ve reflectively collated a range of reviews of my book here.

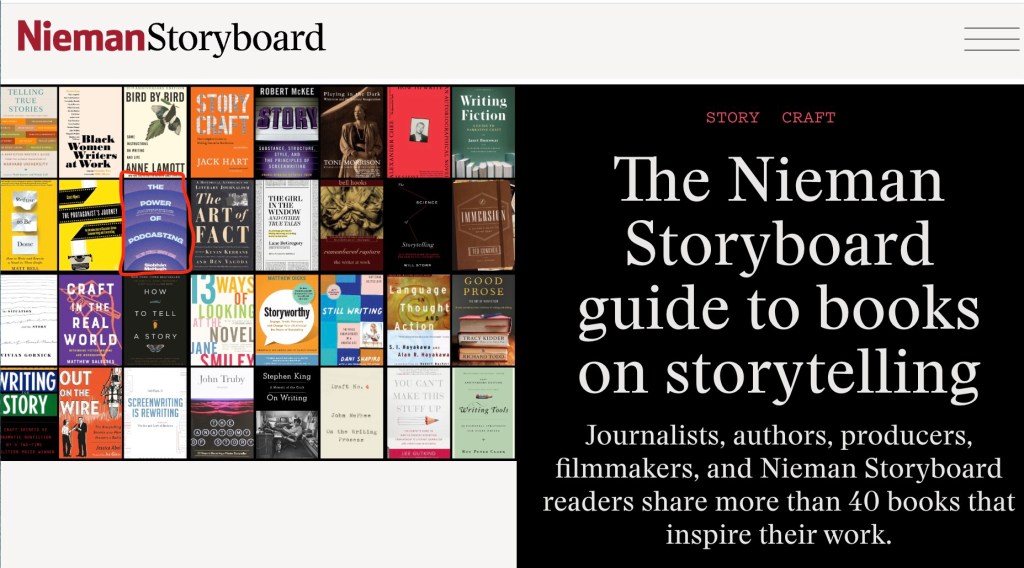

In 2025, I was delighted to learn that my book was included in Harvard’s respected Nieman Storyboard’s recommended Books on Storytelling Craft – along with renowned authors Stephen King, Toni Morrison and … Aristotle!

I’ll freely admit the book is a strange mix: a sprawling /ambitious attempt to understand how podcasting has reinvigorated audio storytelling and ignited an appreciation of the power of voice and sound. One chapter is history, the next is how-to, line-by-line minutiae of actual before and after scripts I’ve worked on and an unpacking of the invisible teamwork that makes a premium narrative podcast sing. There are deeply personal anecdotes, professional insights and academic musings. There are wildly unscientific assertions, such as my belief that audio folk are in general a better class of media person, with a tendency to be more empathetic and decent.

The common denominator is my passion for all things audio (purple cover is a clue). But really the style and scope reflect my own varied experiences across 40 years’ immersion in audio, first as a radio producer in RTE in Dublin, then as a freelance documentary-maker with ABC Australia, then a transition to academia and the painful journey to theorise what was previously a purely practical/intuitive/creative pursuit – and finally the glorious new era of the podcasting revolution, which for narrative podcasts took off with Serial‘s explosion onto the scene in 2014. Now I’m in the happy position of being a maker/creative AND a theorist/critic, a teacher AND a researcher, but most of all perhaps, an evangelist for audio storytelling and the power podcasting brings to that.

PIC: Siobhan back in RTE in 2022 – where the audio journey started, 40 years before.

THE REVIEWS

Matěj Skalický, a Czech radio journalist and academic writing in Media Studies: A Journal for Critical Media Inquiry, embraces the non-linear, not easily categorised nature of my writing about all that. And even laughs at my jokes! He does admonish me mildly for not paying more attention to the Polish literary reportage tradition (sorry Poland! Maybe the sequel he suggests?), but otherwise – what more could you ask than this thorough and perceptive review? A rare and special moment, to feel heard.

McHugh’s book is a wonderful contribution to the global research of podcasting. In its many insightful stories about well-known podcast series, it acts as a manual of what a narrative podcast should be and how to make one. While the book eschews pure scholarly language and its lack of quotation style makes it less acceptable in traditional academia, it is ultimately also much more enjoyable to read.

Matěj Skalický, ‘WHY DO WE ALL LOVE PODCASTS?’

The analysis of the author’s podcast series is the most valuable part of the book, revealing the behind-the-scenes procedures of making an award-winning podcast. By showing the characteristics of intimacy and authenticity, the specifics of narrative and storytelling, the evolutionary development from radio broadcasting, and the triumph of targeting the younger audience, McHugh allows the reader to truly understand the power of podcasting. The questions of why everyone loves them so much and how to make them are not so mysterious anymore. McHugh shows the power of podcasting and allows the reader to harness it, as promised; everyone who reads the book will fully understand what a complex, yet flourishing phenomenon podcasting is. And what is more, as McHugh notes, it is also God’s gift to ironing.

I also appreciated this long and insightful piece by Astrid Edwards in The Australian Review of Books, which credits my book with arguing for (the best narrative) podcasting as a literary/art form.

The strength of the work is clear when exploring the history of the medium. These sections are, to put it simply, fascinating. There is a dearth of information (whether written or audio) about the evolution of podcasting as a storytelling medium, and McHugh provides a tantalising entry point. For lovers of storytelling – whether fiction and non-fiction – these in-depth sections are a delight. McHugh delves into the history of radio (including news commentary and sports broadcast) to explain the elements of podcasting as an artistic medium.

Astrid Edwards in The Australian Review of Books

Podcasting is also a form of literary journalism… McHugh’s analysis of how the New Journalism movement of the 1960s and 1970s influences narrative podcasting today begs to be read. The Power of Podcasting is a reminder that audio storytelling is an art form. It can change minds and influence opinions, and its reach is vast.

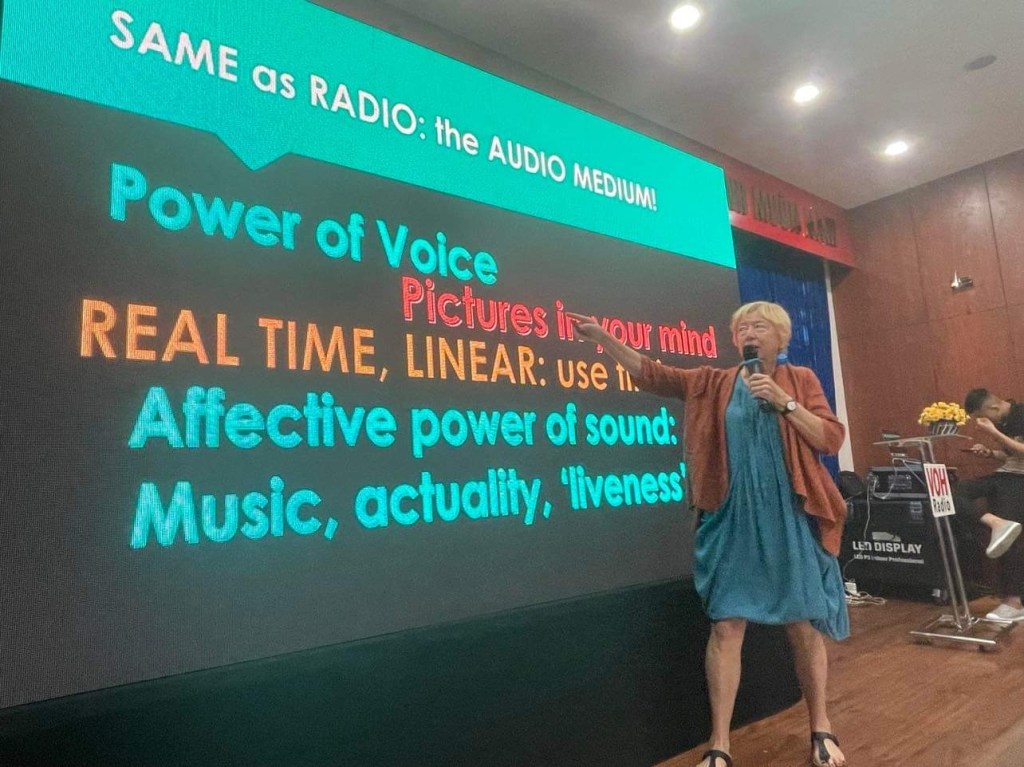

PIC: Siobhan giving a talk on narrative podcasts at the National Radio Festival of Vietnam, 2022

ACADEMIC CRITIQUES

Reviews in academic journals, all positive, interestingly took different perspectives. Writing in The Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast and Audio Media, Gurvinder Aujla-Sidhu notes that I set out to distil the magic of narrative podcasts. She concludes: ‘She certainly achieves that, her passion and knowledge for audio storytelling captures the reader.’ A former radio journalist-turned academic, Gurvinder is buoyed by my rash advocacy of audio makers:

I particularly liked the assertation [sic] that ‘we storytelling folk are generally a good bunch, softer than the average media apparatchik, more inclined to care about fairness and social justice’. It is a point that stayed with me after reading it; good journalists need to be empathetic and have people skills in order to tease out highly personal and often private stories out of individuals. Within podcasting the host/presenter needs to understand that storytelling in audio is an intimate art. People trust podcasters with their precious memories, stories and experiences and the skill is how that story is brought to life.

Gurvinder Aujla-Sidhu in The Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast and Audio Media

Gurvinder also singled out my book’s attention to diversity and social inclusion in podcasting.

This makes this book stand out from others on podcasting as the overview is global in its outlook and is genuinely interesting because the developments are occurring in real time… Chapter 9 offers a deep dive into the drive to include diverse voices in the podsphere. There is an examination of the podcast market in China, a look at diversity at the BBC, PRX and The Equality in Audio Pact and its impact upon The Prix Europa.

Reviewing in Portuguese for Radiofonia: Revista de Estudos em Mídia Sonora, PhD candidate Helena Cristina Amaral Silva is buoyed by my focus on sound. A rough translation: ‘It is with a keen eye on the seductive power of sound and the countless possibilities that the use of sound elements offer to podcasting productions that the author turns, in the work, to storytelling podcasts.’ Silva concludes:

The work presents a broad overview of productions in podcasting of a storytelling type, and constitutes a reference for researchers, professionals, amateurs and other people who are interested in the subject…The debates outlined show the innumerable challenges of the sector, but also shed light on the many possibilities offered by podcasts, productions that since their beginnings demonstrate potential for promotion of diversity, inclusion and voices that do not find space in the mainstream media.

Helena Cristina Amaral Silva in Radiofonia: Revista de Estudos em Mídia Sonora

Manuel Álvaro de La-Chica Duarte a PhD candidate in podcast studies at the University of Navarra, Spain, who is researching the role of the podcast host, is interested in the how-to aspects. Writing in Austral Comunicación, he notes:

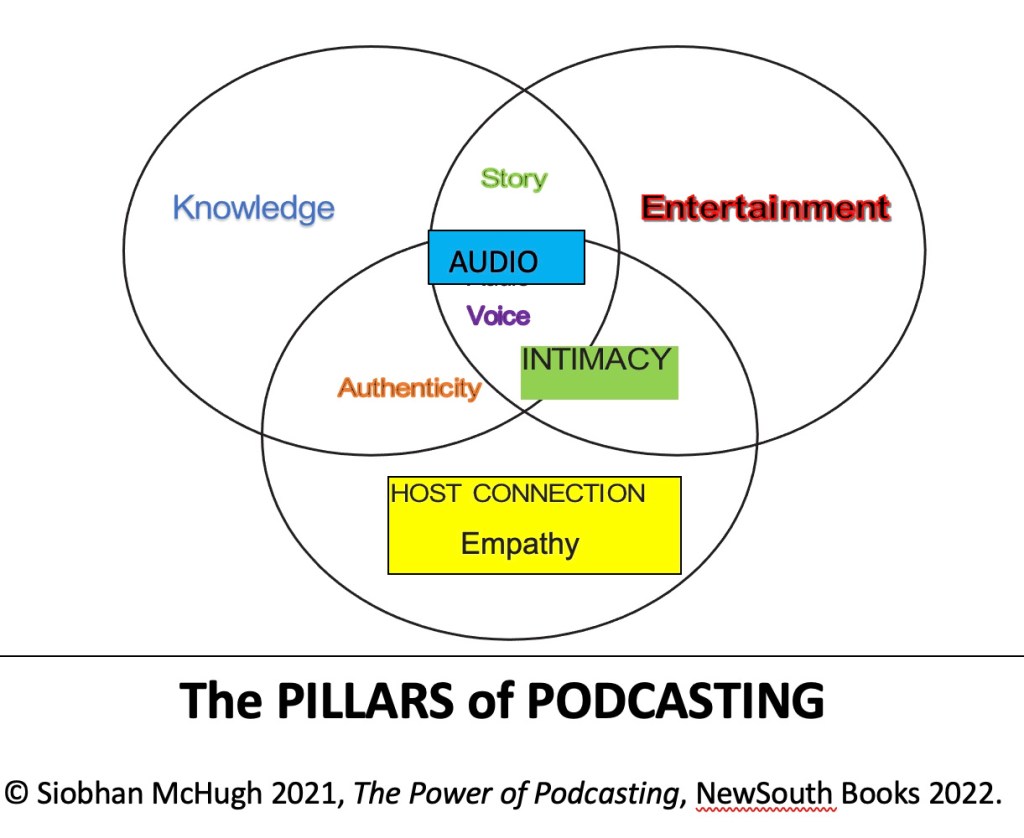

McHugh propone un gráfico con el que muestra lo que ella denomina «los pilares del podcasting». Según su esquema, el poder dela voz reside enla unión de tres elementos: el conocimiento, el entretenimiento y la empatía que construye el anfitrión del programa. Estos tres elementos-que llevan directamente a pensar en el logos, pathos y ethos de la retórica clásica- McHugh los interrelaciona también para destacar otras características de los podcasts.

Manuel Álvaro de La-Chica Duarte in Austral Comunicación

McHugh proposes a graphic showing what she calls “the pillars of podcasting.” According to this scheme, the power of the voice resides in the union of three elements: knowledge, entertainment and empathy that the host of the program builds. These three elements -which lead directly to thinking about the logos, pathos and ethos of classical rhetoric- McHugh also interrelates them to highlight other characteristics of podcasts.

En definitiva, McHugh ha escrito un libro sobre podcastque, por su propia forma de narrar, podría ser un podcast, puesto que lo escribe desde esos tres pilares que menciona al principio de su obra. Por un lado, ella misma forma parte de la historia que está contando. Por otro, utiliza un lenguaje muy oral para mostrarse cercana y construir una intimidad con el lector. Y, al mismo tiempo,cuenta desde la autoridad professional le da el haber formado parte del equipo de producción deesos podcastspremiados. Además, la elección de escribireste libromezclando reflexión con casos concretos es un recordatorio continuo de que, por mucho que se analice el medio,no hay reglas de oro para el éxito de un podcasty cadauno de ellos debe buscar la forma de conectar con sus audiencias en sus circunstancias concretas.

Manuel Álvaro de La-Chica Duarte in Austral Comunicación

McHugh has written a book about podcasts that, due to her own way of narrating, could be a podcast, since she writes it from those three pillars that she mentions at the beginning of her work. On the one hand, she herself is part of the story she is telling. On the other, she uses very oral language to be close and build intimacy with the reader. And, at the same time, it comes from the professional authority of her having been part of the production team of those award-winning podcasts. In addition, the choice to write this book mixing reflection with specific cases is a continuous reminder that, no matter how much the medium is analyzed, there are no golden rules for the success of a podcast and each one of them must find a way to connect with their audiences in their specific circumstances.

In Australian Journalism Review, veteran digital media analyst and PhD candidate Margaret Cassidy writes:

Siobhán McHugh is uniquely placed to write this book. She is both a highly respected and award-winning audio and radio producer and an audio studies academic and practical audio skills trainer. As a well-honed storyteller, she uses an informal style, personal anecdotes and content reviews to introduce the reader to many of the great audio producers around the globe and their works.

Margaret Cassidy, Australian Journalism Review

The Power of Podcasting is both a practical examination and a brief history of the relatively new audio medium of podcasting. This combination provides not only an absorbing introduction for media scholars and practitioners who are entering the field of audio storytelling, but a useful textbook for audio and podcast undergraduate classes and a fascinating read for both industry practitioners and keen listeners. However, beyond this, McHugh’s book is first and foremost a love letter to long-form audio storytelling.

A review in H-Net for the H-Podcast (a site I’ve only just stumbled across) celebrates my ‘narrative /memoir’, declaring (perhaps over-stating!) that ‘Siobhan McHugh has been an integral part of podcasting’s evolution since her foray into radio in 1981.’ Reviewer Dan Morris continues: ‘The Power of Podcasting recounts the incredible journey podcasting has taken from its birth through today. While that tale could be told by many, hearing it from someone with such intimate knowledge brings a sense of warmth and personality. It is like unearthing a time capsule and being part of the action all at once.’ I do like that descriptor – I am still actively making podcasts (The Greatest Menace dropped a cracker bonus episode in February), but I also draw on decades of tradition and best practice. Dan goes on:

To tell the full story of podcasting she has created four distinct narratives… the history and evolution of podcasting, the art of crafting an audio story, lessons for podcasters, and McHugh’s personal experiences. The Power of Podcasting draws you in from the very first words. McHugh storyboards a plotline from an audio editor’s point of view and explains the options she has in building that story… The creation of a soundscape, interviewing skills, the use of pauses to add emphasis, and deciding how to cut interviews down to mere phrases are all explored in great detail throughout the book. Sometimes it feels like the reader is getting a front row seat to the greatest behind-the-scenes moments of podcast editing.

Dan R. Morris, H-Podcast, H-Net

McHugh’s memoirs constitute the book’s third plotline. Few have been as involved as she was in the evolution of the medium. Stories she has worked on, memorable interviews, impactful moments of podcasting, and highlights of award-winning podcasts are peppered throughout the 282 pages.

And in RadioDoc Review, where I have stepped aside as editor for now, reviewer Robert Boynton, Professor of Literary Journalism at New York University, notes that my book ‘begins from a place of sheer wonder’.

It ‘brings the reader in the process of creating a podcast, with all the economic and social challenges that entails.’ This ‘audio-first’ book ‘considers podcasting as a cultural phenomenon, embedded in the practices of journalism and nonfiction storytelling… McHugh writes as a practitioner with an insider’s understanding of how podcasts are made.’

Robert Boynton, RadioDoc Review

It’s wonderful to know that the book is appealing to such a wide audience. It was not written as a strictly academic text, but it is deeply researched, and universities are using it to support their teaching of podcasting. Among them are Muhlenberg College, PA, USA; Toronto Metropolitan, formerly Ryerson, Canada; University of Sheffield, UK; University of Sydney (800 podcasting students across four courses), University of Technology, Sydney; Macquarie University, Sydney and RMIT, Melbourne, Australia.

PIC: Siobhan delivering a guest lecture, University of Sydney, 2023.

I particularly like when my work crosses over to industry and beyond, to general podcast listeners. I was amused to see award-winning Sardinian indie podcast producer Cristina Marras tweet that my book was ‘incredibly approachable’, DESPITE (my caps) my being an academic.

And when I stumbled across this review on Amazon, from someone totally new to podcasting, it made my day. Thank you debs 1221!

5.0 out of 5 stars A Must-Have for Getting Up to Speed on Podcasting

New to the podcast landscape I found this book to be a great resource to learn a timeline and history of podcasting with some wonderful and interesting anecdotes along the way. The author provides a list of great resources available online, in book form and podcasts of great interest. I know I still have a lot to learn about podcasting but feel that this was an amazing pick to take my first foray into podcasting. One word of advice, bookmark or jot down important things you want to remember and research more about later. I’m now combing back through the book to find the many things I told myself I’d explore later but when the list kept growing, it became harder to recall… It’s an amazing contribution–highly informative plus an enjoying read!

debs 1221 – reviewed in the United States on 27 February 2022

See more book reviews/comments, from podcast studies scholars and noted podcast industry people, here.

TALKS/MASTERCLASSES/KEYNOTES/SEMINARS/CONSULTANCY

I am open to speaking engagements, and teaching/research offers, in the academy and/or industry. I am also available as a consulting producer, to advise on narrative podcast development and production. Contact me at podcastpolly@gmail.com for rates and availability.

PIC: The Greatest Menace wins a Walkley Award, Australia’s highest journalism award, 2022. Siobhan is with TGM co-creators Patrick Abboud (also host) and Simon Cunich, and Paul Horan, Audible Australia.

This article offers in-depth, time-stamped criticism of the craft, scripting, hosting, research and production aspects of these storytelling or narrative podcasts, with illustrative audio examples. See also my (short) review of Trojan Horse Affair in the Sydney Morning Herald.

By Siobhán McHugh

Reprinted from RadioDoc Review, 8 (1) 2023

There are many ways to ruin a narrative podcast. As a consulting podcast producer and avid podcast listener, I have heard quite the range. Some, unaware that audio is a linear and temporal medium, present unlistenable works-in-progress: turgid, untextured aural stodge. Others serve up a rambling screed where lazy scripting and poor structure undermine nuggets of insightful journalism. Hosts who do have a compelling storyline can sound alienatingly wooden or sarcastic; and music seemingly selected by algorithm can massacre a story’s emotional heart.

The good news: skilled producers, story editors and sound designers can rescue these efforts and work with would-be hosts to make audio-friendly content. Narrative sense can be conferred by simple punctuation, as in print—but in audio, you might do this using a beat of silence, music or sound, to switch narrative direction or let a statement land. An interview clip might need to be interpreted by you, the host, to tell us the context, the way this voice fits with the other story elements; or it might sit better as a sharp counterpoint to another voice, the meaning heightened by the bald sequence. These are some of the discussions that inform the collaborative art of creating the kind of storytelling podcast that keeps a listener listening.[1]

The deployment of all these elements—voice, actuality, music, archival sound—in the service of story makes a big difference to how engaging the podcast will be. Underpinning all of this are the script and narrative structure: the host should fully inhabit the script, tweak it till it sounds real, for them. The script also has to link, foreshadow and clarify the various story elements, while the narrative arc works at both a micro level, providing a satisfying journey within each episode, and a macro, whereby thorny details and bum steers are explored, eliminated or developed, and by the end of the series, finally resolved—or at least exhausted.

Non-narrated audio, or montage, in the hands of a deft producer is its own art form.[2] But in a conventional narrative podcast today, the listener is guided by the host. If they let us know their thoughts on what they are uncovering, it’s a bonus—we are included now, on this quest. Unlike chatcasts, where listeners are exposed to everything from echoey bathroom-like acoustics to crisp on-mic delivery, technical quality matters in storytelling. Intimacy, that cherished currency of podcasting, starts with a close mic.[3]

Intimacy, that cherished currency of podcasting, starts with a close mic.

Earlier, before important interviews were recorded, there were probably team meetings to nut out a rough episodic structure. This is often conceived with a taut ending and a slow, unfolding opening—a scene or character to intrigue, lead into the story. Once all (or most of) the interviews have been gathered (and usually auto-transcribed[4]), the host, producer and narrative consultant /producers will shape an episode script and annotate it with sound ideas, from archive to actuality. They will worry away, filleting clips, rewriting a word or phrase for coherence, clarity and flow. Someone might suggest a re-sequence, moving a section around to raise stakes, or add tension. Bits get shifted to another episode or deleted. General ideas for sound design are added, along with suggestions for music and what it’s for: a mood shift, a rise in tension, a beat (short or longer) for effect.

Over-juicing someone’s speech with manipulative music is a cardinal sin that can turn poignant into mawkish.

In studio, the host records narration and a first audio draft is built. Sometimes the producers listen without sound design, judging only script and story, flow and feel. Maybe the host sounds lifeless or is getting the intonation wrong; the script might need fine-tuning for the ear. After the sound design is mixed, more adjustments follow. The music might overwhelm or undercut the content: ‘over-juicing’ someone’s speech with manipulative music is a cardinal sin that can turn poignant into mawkish. Sometimes tone is fine but timing is off. An episode that drags needs surgical intervention.

On it goes, draft after draft, for as long as budget and schedule allow. Then one day, it drops online—and listeners decide whether to choose this, out of the over five million podcasts available. A trailer helps get their attention: a precis or titillating taste of what lies ahead. And so, it transpired that I listened to trailers for three narrative podcasts on a China-related theme and opted to press play. My response follows.

***************************************

It’s unusual and welcome to see not one, but three, well-produced narrative podcasts made in the West about China. All provide strong context on Chinese history and politics but focus essentially on an individual: The King of Kowloon (produced by the ABC, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation) memorialises an eccentric graffiti artist called Tsang Tsou-choi, his art seen in the context of Hong Kong’s shrinking democracy. Both The Prince (by The Economist) and How To Become A Dictator (by The Telegraph) zero in on Xi JinPing, President of the People’s Republic of China, their release coinciding with the fifth annual Communist Party Congress in October 2022, at which Xi was expected to be anointed as supreme leader in virtual perpetuity (spoiler: he was).

The Prince (also referred to hereafter as Prince) and The King of Kowloon (KOK) both open with a theme of disappearance: in the former, Xi inexplicably goes missing in 2012, just before his leadership takes off. In KOK, Tsang Tsou-choi’s ephemeral art is here one moment, gone the next. How To Become A Dictator (Dictator) starts with a more conventional ‘scene’: host Sophia Yan is trying to get a flight back to China, where she has been working for ten years as The Telegraph’s correspondent.

All three podcast hosts are female journalists with a Chinese background, but we find them in very different contexts. Prince host Sue-Lin Wong was born and raised in Sydney, of Malaysian heritage. Now in her mid-thirties, as a student, she was a notable all-rounder: competitive athlete, volunteer surf lifesaver, debater, musician, dux of her high school. She headed to China in a gap year to learn Mandarin, then to the Australian National University to study Law and Asian Studies. She worked as a journalist with Reuters and the Financial Times before joining The Economist and having to leave Hong Kong along with other international journalists during protests in 2021, as surveillance increased. Remarkably, The Prince is her first podcast.[5]

Louisa Lim grew up in Hong Kong with a white English mother and a Singaporean Chinese father. Raised in an English-speaking enclave, she ‘was made by the city. I was shaped by Hong Kong values, in particular a respect for grinding hard work and stubborn determination’.[6] Lim speaks ‘basic Cantonese’ and was China correspondent for the BBC and NPR for a decade. Her first book,The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited , was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize for Political Writing. She co-hosts The Little Red Podcast, an award-winning podcast on China, has a PhD in journalism studies and is senior lecturer at the University of Melbourne. She also hosted an insider ‘how-to’ podcast, Masterclass, in which she interviewed top audio professionals about best-practice audio journalism and podcasting.[7] Her recent book, Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong, was a finalist in the prestigious Australian Walkley awards for excellence in journalism.

Taiwanese-born Sophia Yan is based in New York when not on assignment. An award-winning journalist who has been a China correspondent for ten years, she previously made the podcast Hong Kong Silenced (2021), ‘the inside story of how life in Hong Kong was turned upside down in just one year’. In The Panic Room (2022), she interviewed people about how they surmounted curveballs and challenges. Like Prince, Dictator was conceived as a biographical analysis of Xi: inevitably, both cover similar ground. We hear the same archival audio (e.g. Xi giving a bullish speech in Mexico in 2009) and traverse Xi’s policy decisions, from his crackdown on corruption, big and small (hunting ‘tigers and flies’) to his infamous repression of the Uyghur minority. The two podcasts differ, however, in host style and scripting, whom they interview and how they revisit key moments, such as Xi’s stint living in a cave as a young man ostracised by the party. Their content is also governed by structure and length: Prince has eight c. 35-40min episodes, totalling about five hours, while Dictator has four 35–44-minute episodes, totalling under three hours. KOK is around three hours, comprising six approximately 28-minute episodes: unlike the other podcasts, produced by newspapers as digital-only content in which an episode can be as long as it needs to be, KOK was also broadcast on ABC Radio National and was constrained by a 30-minute broadcast slot.[8]

The following analyses aspects of the podcasts’ approach, from production/structure and craft/sound design to editorial/research, hosting and script.

HOSTING: SCRIPT and SUBJECTIVITY

The more relatable a podcast host is, as a human being and in connection to the podcast theme, the more listeners are likely to engage. Academic research is starting to confirm this anecdotal dictum: a recent Danish study found that listeners ‘take comfort in podcast hosts who self-disclose by showing vulnerability, authenticity, and humour, and who share their own point of view’.[9] In practice, the importance of this parasocial relationship in podcasts was emphatically established by audience reaction to classics from true crime juggernaut Serial (2014) [10] to The New York Times’ hit news show The Daily (2017).[11]

Serial host Sarah Koenig was reluctant to bring herself into the narrative at first. But as her colleague, executive producer Julie Snyder explained: ‘The story really lived in the details [but] the details, a lot of the time, felt a little dull… And when Sarah told us what she was doing or thinking, and the significance of it, it was “Oh, I see.” And then there were also other times when Sarah told us what she didn’t know, and I thought it was kind of ballsy and… emotional.’[12]

Koenig developed a spontaneous-sounding style that included little conversational asides, as if she was mulling things over in the moment with a friend (us, the listener). For example, in episode six, she’s considering a potential witness, whom she dubs ‘The Neighbour Boy’.

The Neighbour Boy never shows up at trial. He’s never mentioned. So I let it go. But, you know, it is weird. And if Laura’s story is true, then there’s another witness to this murder. It’s one of the things about this case that kind of bobs above the water for me, like a disturbing buoy.

This offhand language (‘kind of’, ‘you know’) is miles away from the stiff newsreader voice of authority. It’s beguiling—we feel that she is taking us into her confidence.

The charismatic host-on-a-quest is now an established podcasting trope. The tone might be cheeky, such as Marc Fennell in Stuff the British Stole, charmingly persuasive, such as Patrick Radden Keefe in Wind of Change, or revelatory, such as Afia Kaakyire in S***hole Country. But importantly, where the host is conducting investigative journalism, core narration still needs to be grounded in solid fact. ‘I don’t think you can get away with it if you haven’t done your homework’, warns Koenig. ‘Even when it sounds like I’m kind of casual in my interpretations of things, I’m not. My observations were based not only on my reporting but on the documentation that exists in the case.’[13]

The hosts of TP, KOK and Dictator have clearly done their homework.[14] The podcasts are rich in historical detail and sharp political analysis, reflecting the hosts’ years of immersion in China-related affairs, but their tone and host persona are distinct. Prince’s Sue-Lin Wong comes across as infectiously curious and smart verging on sassy. Discussing how the Chinese Communist Party indoctrinates its 100 million members, she asks: ‘How do you get them all on the same message—your message?’ We hear audio of an electronic device. Wong clarifies: ‘It turns out there’s an app for that’. After providing detail on how the Xi JinPing Thought app codifies its propaganda, Wong explains: ‘Party officials must use the app daily. They get a score—it’s a sort of ideological fitness tracker.’ These sort of short, snappy sentences work well in audio, and provide a useful contrast to the more subtle explorations Wong conducts with interviewees, who range from journalists and academics to eye witnesses such as a woman who knew Xi as a child. As narrator, Wong talks a bit fast at times, but mostly we are swept along by her energetic approach.

Wong occasionally inserts herself into the story, recalling how she reported from Beijing on the Olympics in 2008, and visiting a home in Muscatine, Iowa (Ep 7) where Xi stayed in 1985 on his earliest American visit, as a lowly regional official. Xi is still recalled with affection by the earthy owner, Sarah Lande, who provided his first encounter with popcorn and who welcomed him back there in 2012, when he was a distinguished guest of President Obama. Besides providing a surprise window on Xi’s life and a welcome contemporary scene in a podcast so focused on history, Wong skilfully weaves this incidental detail into a narrative transition that sets up a major expository shift.

A lot’s happened since Xi Jinping first tried popcorn in Muscatine. In the subsequent years, the Chinese Communist Party watched as America abetted the collapse of the Soviet Union—a seismic event for the party and Xi Jinping himself. The Tiananmen Square democracy protests in 1989 only added to their fears.